Misty Keasler |

|

|

|

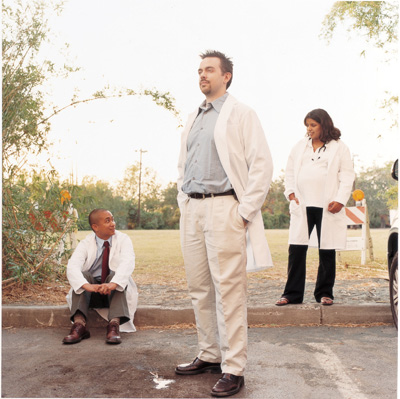

Pediatric resident Jay Gardner, MD, (center) and colleagues Larry Montelibano, MD, (left) and Sonal Saxena, MD, cleared brush from this area behind Children’s Hospital New Orleans to create an ad hoc helipad. |

Jay Gardner, 28, a third-year pediatrics resident at Louisiana State University, was one of 400 employees and medical staff who rode out Hurricane Katrina at Children’s Hospital New Orleans, sleeping at the hospital, caring for his tiny patients in intensive care and staying behind after his own family and friends had been evacuated from the city. Like everyone else, he was just doing his job.

In a phone interview in October, Gardner, who grew up in Shreveport and has lived in New Orleans for the past 10 years, talked about the experience of staying behind, caring for patients and ultimately helping to evacuate Children’s Hospital following Katrina’s destruction of New Orleans:

SUNDAY, Aug. 28: Katrina is declared a Category-5 storm, the highest rating.

Related story: |

|||||

I was activated for code gray at 3 p.m. before the storm. If you were activated, you had to stay. If you don’t, that’s desertion. Kelly, my wife, left that morning for Baton Rouge to stay with her parents.

I was pretty nervous. My wife was extremely upset. She was crying because she felt guilty leaving me behind, and she wanted me to come with her.

Getting to the hospital was fine. It was partly cloudy, no big deal. That evening it started to rain. Further into the night, it progressively got heavier. The hospital had put all these metal sheets up that covered all the windows, so you couldn’t see outside. We watched the hurricane on TV hoping there would be a last-minute turn.

Then went to bed around 11 o’clock.

I remember waking up a couple of times in the night. You could hear the howl of the wind. Up and down, up and down. It was constant. I tend to be a heavy sleeper, so I got some sleep, but other people didn’t sleep too well.

MONDAY, Aug. 29: 6 a.m. Katrina makes landfall on the Louisiana coast. Several levees in New Orleans fail, flooding parts of the city. High winds rip holes in the roof of the Superdome stadium, which is housing thousands of evacuees. Dozens are reported dead in Mississippi.

At about 4 or 5 a.m. we lost power. The air conditioner went off. Our generators turned on.

Got up that morning. I went to see my five patients. Most of them were infants and small children.

I had one 17-year-old girl who was pretty nervous. She couldn’t get in touch with her family. She had suffered a tear in the esophagus several days before the storm and had such horrible bleeding, we had to endoscopically cauterize it. She almost died and still needed inpatient care.

The patients’ parents were kind of worried about everything. Most of the patients had one or two parents staying with them at the hospital. Children’s Hospital stayed pretty much intact. Still, everybody was pretty upset. Around that time, rumors started circulating. That the Superdome was damaged.

That there were all these people stuck in New Orleans. That there was looting. By the afternoon, the weather started calming down. I went outside. You could see the wind ripping things around, all the small debris. Children’s is right next to a levee, but it’s one of the highest points in New Orleans.

Still, we were worried about flooding. The most upsetting part was when you saw what happened to the city. We were watching it on TV.

By that evening the weather really started to calm down. That night, I remember walking outside and looking around the neighborhood. Pitch black.

No lights. It was like camping. It was the first time I’d ever seen stars in New Orleans.

TUESDAY, Aug. 30: Attempts to plug a two-block-wide breach in a levee at the 17th Street Canal fail. Eighty percent of the city is flooded. Looting is widespread. More than 12,000 people are in the increasingly uninhabitable Superdome.

Another resident and I decided to check out our homes that morning. We both live about five minutes from the hospital. Trees on the ground all over the place. Power lines and cable lines, too. Some shutters and roof tiles were torn off. It was surreal. My place was fine. My friend’s place was OK too.

On and off during the day I would call my wife. Sometimes cell phones would work. Usually I would call her every hour.

That evening around 7 p.m. we had a huge open meeting with administration to let us know that they were bringing in more diesel fuel, linen service, food service. Supplies to last about a week.

About 30 minutes after the meeting the mayor went on the TV and said the levees broke, the city was going to be flooded. We had to get the kids out of the hospital as soon as possible and evacuate. But it was too late and too dangerous that night. We teamed up and went through all of our patients deciding which we could discharge. Some were ready. Then there were the NICU [neonatal intensive care unit] babies and the oncology and hematology kids who were very sick and would be difficult to move. We were trying to get a plan together. I got to bed about midnight.

WEDNESDAY, Aug. 31: Looting and violence in New Orleans intensifies. New Orleans police abandon search efforts to attempt to control violence.

Thirty of our inpatient kids were airlifted to facilities in Houston, Miami, Arkansas, Lafayette from the homemade helipad behind the hospital. Most of those were ICU kids and hematology patients. Ambulances and helicopters came in and out through the day and night. We used generators for lights outside.

For the other patients who weren’t in critical situations we caravanned them out using our own cars. About 25 residents, fellows, staff — we all drove these kids to the [Louis Armstrong New Orleans International] airport. Kansas City Children’s Hospital was sending in transport planes to the airport to pick them up.

I took two of my kids in my car: the 17-year-old girl, who still hadn’t been able to contact her parents, and a 1-year-old baby who had her grandmother with her. The baby had short gut syndrome; she’d been in the hospital for a month. She was yellow with jaundice. Her grandmother comforted her. She did all right.

The airport looked like a military base. We handed over the patients, just handed over their whole charts. And then we drove back to the hospital. We passed thousands of people waiting to be evacuated, hundreds of buses, fire trucks, police cars, disaster recovery people.

It was nightfall when we finally got back. By then I was pretty nervous. There was nobody on the road. I got to bed back at the hospital at about 9 p.m.

THURSDAY, Sept. 1: National Guard troops help evacuate the Superdome.

By that morning we pretty much had all our kids out. The administration came on the loudspeakers at 6 a.m. and announced: “Attention all personnel. Everybody needs to leave the hospital.” We all got upset and frustrated at times throughout the week. Some people got pretty emotional through it all. But by Tuesday night our sole purpose was to get the kids out of the hospital. None of our children died during the code gray, a truly monumental feat. After that, we knew there was no point in hanging around. We got in our cars, grabbed our clothes and left. That was about 7:30 a.m. We drove out of the New Orleans area and back into regular civilization, got gas and went our separate ways.

I never got real upset until I was finally driving out of New Orleans. Everything was deserted. It was just a ghost town. It was one of the worst feelings I’ve ever had.

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at