Their weapon? A new kind of vaccine

Denny Liggitt,

DVM, PhD |

|

|

|

|

By ROSANNE SPECTOR

Worried about the avian flu? Stanford immunologist and infectious disease clinician David Lewis, MD, is. That’s why he’s madly fine-tuning a new type of vaccine. He’s hoping it will protect humans from the illness before the virus mutates into a form that spreads easily from person to person.

Traditional vaccines have a lengthy production time; the process includes five months of incubation inside a chicken egg. But the rapid mutation rate of the flu virus calls for a response measured in days.

The new method, which could be used not only for avian flu but most any infection, would allow manufacturers to produce a dose of flu vaccine in under a month, says pediatrics professor Lewis. He and fledgling biotech company Juvaris BioTherapeutics of Pleasanton, Calif., received a $1 million federal grant in January to continue studying the vaccine and test it against the most virulent form of bird flu, the H5N1 strain, at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lewis has no financial relationship with the company.

Denny Liggitt,

DVM, PhD |

|

|

|

|

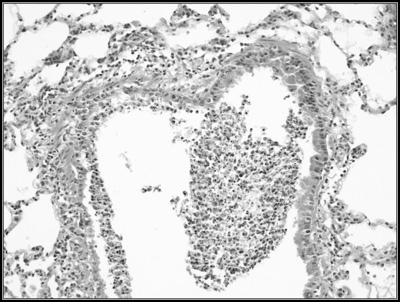

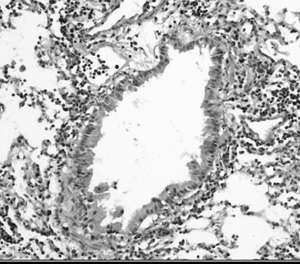

The key to the team’s approach is a new type of “adjuvant” or additive that boosts vaccine potency. This adjuvant is a microscopic capsule, called a liposome, that carries strands of DNA — the precise sequence of which appears unimportant. Once inside an animal’s bloodstream, these cationic liposome DNA complexes, or CLDCs as they’re called, probably enter into dendritic cells, which serve as the immune system’s early warning system.

“Mixing CLDCs and antigen — for instance an avian flu protein — turns on both T-cell and B-cell immunity,” says Lewis. High levels of both types of immunity should be particularly effective at ridding the body of the virus.

Meanwhile, Lewis is exploring the best way to administer the vaccine — comparing oral, intranasal, intradermal and intramuscular routes. He’s also studying its long-term effects on the mouse immune system. “Given its potency, autoimmune disease and exhaustion of the immune system are two concerns,” says Lewis, a clinician at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital.

Normally, human testing would be years away. But with H5N1 avian flu killing hundreds of thousands of birds and more than 80 people since late 2003, Lewis believes the sooner the better.

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at