What's an inventor like Yock doing in a place like this?

Trujillo-Paumier |

|

|

|

By AMY ADAMS

Paul Yock, MD, is a happy man. He smiles easily. He congratulates students in the hallway. He positively raves about his colleagues.

Yock progresses toward downright giddiness when he talks about brainstorming inventions — a regular occurrence in his role as director of the Biodesign Program. “It’s like mainlining for me,” he says. If brainstorming is like a drug, then Stanford is where Yock finds the good stuff. As an inventor himself, a mentor for young inventors and a brainstorming resource to industry inventors, Yock is an addict.

Yock’s work space in the Clark Center even has a dedicated brainstorming room, covered in white boards and with slogans painted high on the wall in place of crown molding: Encourage wild ideas; Go for quantity; Build on the ideas of others. The room’s basketball hoop has seen better days.

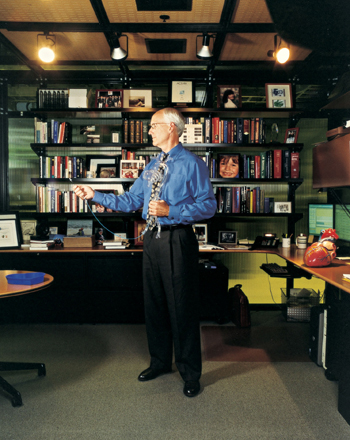

A tall, wiry man, Yock has the graying hair and tasteful attire of a seasoned businessman. Despite his refined appearance, Yock gestures broadly and squirms to the edge of his chair when he talks about inventing.

Yock didn’t start out dreaming about inventions. “I wasn’t a kid who took apart radios,” he says. Instead, he hoped to be an architect. Like many other inventors with a medical bent such as Tom Fogarty (balloon catheter) and John Simpson (balloon angioplasty), Yock ended up in cardiology. “Cardiology is very understandable to someone who likes gadgets. It’s basically plumbing,” he explains.

Squeamishness is what pushed Yock to his eventual love. During a medical school summer research project he needed to measure levels of a transient molecule in rat livers. The lab’s method for this was, according to Yock’s description, unpleasant. At this point in the story he mocks a rat’s startled face when frozen in liquid nitrogen. So he found a way to get the bit of quick-frozen liver he needed without all the unpleasantness. He created a vacuum-assisted biopsy device that sucked out a sample and froze it within a half second.

His next invention arose out of fear of failure. During his cardiology fellowship, Yock’s role in a balloon angioplasty was to hold the end of a 10-foot wire, preventing it from moving more than a quarter of an inch while another surgeon carried out the real work of cleaning out the patient’s heart. “This was a classic no-win situation,” Yock says. “The only noteworthy thing you could do as the fellow was to mess up.” Yock invented his way out of that situation by devising a new single-physician angioplasty system that is the standard angioplasty and stenting system used today.

Related stories: |

|||||

Those first successes were all it took for Yock to develop a habit. He began filling up file cabinets with invention drawings.

He now holds U.S. patents on 44 gadgets, most designed to ease procedures for heart or artery disease. He says much of his success is thanks to being at Stanford, where he holds the Martha Meier Weiland Professorship. “There’s no place in the world even close to this,” he says. Pointing across the street to the engineering campus, “There are unbelievable students coming out of there.”

Combine the strong relationship between the engineering and medical school campuses with close access to industry partners in Silicon Valley, and Yock says it’s a recipe for success.

However, some of Yock’s colleagues view those ingredients differently. For some inventors, university life rankles. The process for getting patents and licensing inventions is often slower than in the private world, and because of schools’ conflict-of-interest policies, restrictions on the inventor’s involvement in testing devices are often more stringent.

For the independent-minded inventor, these rules can be a burden. The classic entrepreneur’s mentality has driven more than one of Yock’s colleagues to more-open pastures outside academia.

Yock thinks university restrictions are all for the good. In fact he thinks it’s so important for inventors to be attuned to conflicts that he and his colleagues in the Biodesign Program have incorporated ethics into the curriculum.

However, he sees possible trouble down the road.

“Our mission at Stanford is translating discoveries, but that pipeline often has to go through industry,” he says. Stanford does a good job of reducing conflicts of interest, he says, but he worries more restrictive policies — along the lines of those recently put in place at the NIH — will limit industry contacts that are crucial for students and faculty to learn how to translate their inventions into products.

Even while discussing these concerns Yock smiles.

With access to the best minds and interesting ideas, life is good for a brainstorming junkie in his position.

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at