A quick look at the latest developments from Stanford University Medical Center

![]() Heady lifting

Heady lifting

![]() Prescribing without a net

Prescribing without a net

![]() Herzenberg wins Kyoto Prize

Herzenberg wins Kyoto Prize

![]() Filling the genetic counseling gap

Filling the genetic counseling gap

![]() Stem cell funds flow in

Stem cell funds flow in

![]() No free lunch

No free lunch

Heady lifting

Krishna Shenoy, PhD, and his team are working on a brain-computer interface that would improve a paralyzed person’s ability to move an object simply by thinking about it.

This summer, the group reported a major step forward: a faster way to process signals from the brain. The new approach, outlined in the July 13 issue of Nature, quadrupled the speed of previous systems, for the first time making an interface fast enough to be practical for patients.

David Plunkert |

|

|

|

Two significant hurdles have impeded developing a workable interface. The first is simply making sense of the signals generated by neurons. The second is interpreting those signals with enough speed and accuracy to make the interface usable.

The basic idea is to implant electrodes in a person’s head to record brain waves and send them to a computer, which translates the signals into commands to control a prosthesis. The standard approach to processing neural impulses has been to collect and translate them every step of the way as the subject thinks about moving the prosthesis from point A to point B. That’s a valid approach if the user is doing things requiring continuous movement, such as drawing a line. But all that collecting and processing slows down the prosthesis.

Shenoy, an assistant professor of electrical engineering and of neuroscience, set out to shorten the process by accurately forecasting an intended target based on the signals the neurons sent out when the subject thinks only about moving an arm to a specific target.

The researchers worked with rhesus macaque monkeys that were connected to the interface by a tiny silicon chip, less than one-tenth the area of a penny, holding 100 electrodes. The electrodes were implanted in the pre-motor cortex, which is on the surface of the front part of the brain and is one of the areas responsible for guiding a person’s or a monkey’s arm.

The monkeys were trained to face a computer screen, with one finger touching a central starting point and their eyes focused on another starting point nearby. When a target spot lit up elsewhere on the screen, the monkey knew that it was supposed to touch the target spot — but only when another on-screen signal told it to. Until the “go” signal was given, the monkey waited.

This waiting period was the critical phase in collecting the data. The monkey’s brain waves during this hiatus simulated the neural signals generated by a person while thinking about moving a prosthetic arm or cursor to a particular place.

The challenge was finding the “sweet spot,” with the best balance of neural processing speed and accuracy. Shenoy’s team ultimately arrived at a result that was far superior to what others had achieved.

“Our research is starting to show that, from a performance perspective, this type of prosthetic system is clinically viable,” confirms co-first author Stephen Ryu, MD, clinical assistant professor of neurosurgery. “But in order for it to be a practical system for a human, it also has to be safe and reliable.” Currently, the electrodes last at most a few years. As with pacemakers before them, the implants will have to last longer before they’ll become widespread. — LOUIS BERGERON

The study was supported by the Office of Naval Research, the Christopher Reeve Foundation, the National Science Foundation, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, the Sloan Foundation, the Whittaker Foundation and Stanford University.

| ![]() Back

to Top |

Back

to Top |

Prescribing without a net

Doctors often prescribe medications despite a lack of conclusive evidence of their effects and safety, a medical school researcher has found.

David Plunkert |

|

|

|

Of a wide sampling of prescriptions dispensed in 2001, 21 percent were intended to treat conditions for which the drugs lacked specific approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, though other research suggested possible benefits. Furthermore, about three of every four of the prescriptions lacking FDA approval were for conditions for which there was little or no evidence of the drugs’ effectiveness.

This practice of “off-label prescribing” offers doctors flexibility and allows them to innovate but also carries risks. The findings, published in the May 8 Archives of Internal Medicine, were based on data from health-care marketing company IMS Health about an estimated 725 million annual prescriptions — the total in the company’s database for the 100 most-used drugs and 60 other randomly selected, commonly used medications.

The results show scientific evidence plays only a partial role in a physician’s treatment decisions, says senior author Randall Stafford, MD, PhD, associate professor of medicine at the Stanford Prevention Research Center.

“Many doctors prescribed a drug when there was little or no evidence supporting its efficacy and safety,” Stafford says.

It is unclear how off-label uses become established. Informal communication between physicians, published scientific studies and pharmaceutical industry marketing could play roles, Stafford says.

Of course, just because a drug lacks the FDA’s blessing doesn’t mean it’s ineffective. The FDA approves drugs for treating specific indications only, and there are many reasons why a drug might lack approval for treating a particular condition, Stafford says.

Undertaking the trials needed for approval, for instance, can be expensive.

If a drug’s patent has expired, a company is unlikely to pursue approval for another indication.

What’s more, many drugs belong to classes of pharmaceuticals that work in similar ways, though each might have different side effects. Other off-label use may represent an extension of labeled uses or evolving new uses that have not been evaluated stringently. Greater caution is advised in such circumstances.

“These off-label uses have not been scrutinized the way FDA-approved uses have been,” Stafford explains. “While this situation is more risky, some patients might have conditions where taking such risks might be warranted.” — ANNE PINCKARD

This study was funded by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

| ![]() Back

to Top |

Back

to Top |

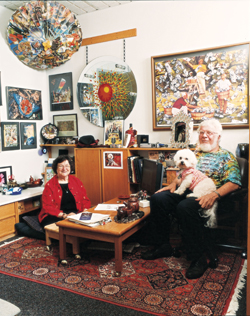

Herzenberg wins Kyoto Prize

In the 1960s, a pair of tired eyes set Leonard Herzenberg on a path that eventually led to a revolutionary scientific technology. “I was sitting in the lab one day counting immunofluorescent cells under the microscope, and I said, ‘There’s got to be some kind of machine that can do this.’” What resulted was the fluorescence-activated cell sorter, or FACS, and it has earned him a 2006 Kyoto Prize — Japan’s equivalent of the Nobel Prize.

Trujillo-Paumier |

|

|

|

|

“I’m extremely pleased and excited to receive the award,” says Herzenberg, PhD, an emeritus professor of genetics. “I only wish it were possible to be shared with my wife and lifelong colleague, Leonore Herzenberg,” who is also a professor of genetics at Stanford.

Kyoto Prizes are presented annually for significant contributions in one of three areas: advanced technology, basic sciences, and arts and philosophy. The official award ceremony will take place Nov. 10 in Japan, where each winner will receive a gold medal and a cash gift of about $446,000.

Herzenberg, 74, won the advanced technology award for developing the sorter, which can tease individual living cells out of a population of trillions, based only on their protein fingerprints. The sorter jump-started the fields of modern immunology, stem cell research and proteomics, and made invaluable contributions to clinical care. It’s now ubiquitous in research and clinical laboratories around the world.

“The FACS is one of the most important medical devices ever developed,” says Philip Pizzo, MD, dean of the School of Medicine. “It provided fundamental insights into the impact of HIV on the immune system and it has been a valuable tool for diagnosing, monitoring and treating HIV/AIDS, cancer and infectious diseases.”

Like a coin sorter that separates a jumble of change into neat stacks of quarters, nickels, dimes and pennies, the FACS makes sense out of chaos. Rather than separating by size, it divvies up cells according to fluorescent tags attached to their surface. Because researchers can couple the tags to antibodies that attach to proteins found only in certain cell types, the sorter can pluck out rarer-than-rare immune stem cells for further study or identify populations of cells that are waxing and waning in such diseases as cancer or HIV. The possibilities of the technology, also known as flow cytometry, are limited only by the creativity of the users.

“As an immunologist, I have often had cause to bless Len for his foresight and commitment,” says Nobel laureate and president of the California Institute of Technology David Baltimore, PhD, who has known Herzenberg for more than 30 years. “So many experiments in modern immunology are possible only because of the FACS.” — KRISTA CONGER

| ![]() Back

to Top |

Back

to Top |

Filling the genetic counseling gap

The explosion of knowledge about the human genome has led to hundreds of new genetic tests that offer clues about a person’s risk of disease. Yet there remains a serious shortage of genetic counselors — the professionals trained to help patients understand the tests’ results.

David Plunkert |

|

|

|

Stanford is responding with a new master’s program — the only one of its kind in Northern California and one of four in the western United States — that will train genetic counselors. The two-year program, expected to begin in the fall of 2007, will train six counselors each year.

The program will be a key part of the medical school’s efforts to translate knowledge from the lab into clinical practice, says Louanne Hudgins, MD, professor of pediatrics and a specialist in clinical genetics, who will direct the new program.

“It continues to get more complicated as we discover more and more. It’s hard for patients, who ask, ‘How do I sort through all these tests and decisions?’ We’re constantly adding to this new reservoir of information,” says Joanne Taylor, a genetic counselor at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital and one of 14 counselors at Stanford.

The role of the counselor is not to advocate one option over the other, notes Taylor, who works in the prenatal counseling program. Rather, counselors educate people and present them with options.

She says 90 percent of the time she can give patients good news. “It’s the other part, the 10 percent, that’s more challenging. That’s why our profession is so important — because we have to help people through a difficult time in their lives when they may not have support.”

It is her job to put results in perspective, Taylor adds.

Nonetheless, Taylor notes that patients may view their risks in different ways. For instance, a woman who became pregnant only after five in vitro fertilization procedures might view a 1-in-300 risk of miscarriage from amniocentesis as intolerably high, while a 25-year-old woman who conceived naturally might find the risk perfectly acceptable, she says.

“Everyone is different, and they need to decide what is best for them, based on their circumstances,” Taylor says. — RUTHANN RICHTER

| ![]() Back

to Top |

Back

to Top |

Stem cell funds flow in

Stanford has selected its first 16 scholars to receive funds for training in stem cell research from a California Institute of Regenerative Medicine grant. The awardees come from 11 departments in the schools of medicine and of engineering.

Last fall, Stanford was one of 16 universities to receive the initial batch of CIRM training grants. The grant, totaling $3.7 million over three years, will fund six graduate and medical students, five MD postdocs and five PhD postdocs.

These 16 scholars, announced in July, will join nine trainees who are already receiving money through the National Institutes of Health to study regenerative medicine.

CIRM was created in 2004 after California voters approved Proposition 71, which provides $3 billion to fund stem cell research, training and facilities in California.

Although the funds are tied up in legal disputes, CIRM raised money to fund 169 scholars through private philanthropy and a state loan. — AMY ADAMS

| ![]() Back

to Top |

Back

to Top |

No free lunch

Stanford has joined a small cadre of major academic medical centers in enacting a policy aimed at limiting the influence of the biomedical industry in day-to-day clinical and educational activities.

Among its key provisions, the policy prohibits physicians and scientists from accepting industry gifts of any size, including drug samples, anywhere on the medical center campus or at off-site clinical facilities where they practice; bans pharmaceutical, bio-device and related industry representatives from patient-care areas and research laboratories except for specific indications; and allows industry support of educational activities only under limited conditions. The policy will take effect Oct. 1, 2006, and applies to School of Medicine faculty as well as community physicians who practice at Stanford Hospital & Clinics and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital.

“We do not want industry dollars to have the potential to influence how we train people or give clinical care,” says Harry Greenberg, MD, senior associate dean for research and chair of the task force that developed the policy. He notes that the medical school already has a strong policy that governs conflicts of interest in research activities.

Larry Shuer, MD, Stanford Hospital’s chief of staff, says he’s sure most medical staff feel their medical decisions are uninfluenced by free pens or doughnuts from an industry representative. “However, we all agree that the appearance of possible conflict is what we must try to avoid, as the public perception may be different from that of the physicians,” he adds.

Stanford is part of the growing effort to manage potential conflicts of interest with industry, especially the pharmaceutical industry. Of the $21 billion the pharmaceutical industry spends every year on marketing, roughly 90 percent targets physicians, through mechanisms such as free meals, gifts, drug samples and sponsorship of continuing medical education programs, according to a 2006 article in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

The new policy is somewhat broader than several others in regulating the medical device, biotech, and hospital and research equipment and supply industries as well as the pharmaceutical industry.

The policy states that companies cannot pay for meals for faculty members or trainees on campus, and it provides guidelines for participation in industry-sponsored events on and off campus. Sales and marketing representatives cannot be present during an educational activity, and no promotional materials can be handed out.

The policy also prohibits faculty from publishing articles that have been ghostwritten by industry representatives, and it reinforces an existing practice that faculty disclose related financial interests in any presentations or published papers.

All residents, trainees and staff must receive training about potential conflicts of interest in interactions with industry — a key provision of the new policy, says task force member Gilbert Chu, MD, PhD, professor of medicine and of biochemistry. “We need to train our students and residents on appropriate conduct. That’s what leads to cultural change over the years,” Chu says. — RUTHANN RICHTER

| ![]() Back

to Top |

Back

to Top |

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at