10 great Stanford inventions

Venture into almost any medical research laboratory or clinical setting and you’re likely to find at least one piece of equipment with Stanford roots. Innovators from throughout the university have come up with dozens of devices that have transformed research and improved human health.

Although Stanford’s contributions span a variety of fields — from biotechnology to computer science to bioengineering — Stanford Medicine is focusing here on medical devices and instruments, including technologies for improved diagnosis or characterization of diseases. Below is a quick look at 10 significant medical technologies that were invented by people who were working at Stanford when the inspiration struck.

Atomic force microscope

Steve Gladfelter |

|

|

|

Inventor: Gerd Binnig, PhD, IBM fellow emeritus (co-inventors Calvin Quate, PhD, emeritus professor of electrical engineering, and Christoph Gerber, PhD, of IBM)

How it began: Optical or electron microscopes provide two-dimensional, magnified views of an object, but not the vertical dimensions of an object’s surface. In 1985, Binnig was working in Quate’s lab on a method that would provide 3-D images at magnifications high enough to view single atoms on an object’s surface.

What it does: The atomic force microscope makes images of surface topography by dragging a pointy tip over a structure’s bumps and folds. The tip reads the shape like a blind person reads Braille, and the textures are then translated into a visual image. The AFM measures surface deflections as small as one-tenth the diameter of a silicon atom.

Impact on medical science: In the biological sciences, AFM has produced images of DNA, single proteins, structures such as gap junctions and living cells. AFM tips coated with enzymes act as biosensors that monitor the ability of chemicals to permeate diseased and healthy tissues.

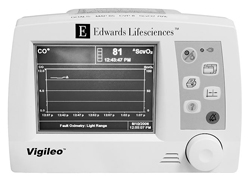

Continuous cardiac output monitor

Steve Gladfelter |

|

|

|

Inventor: Mark Yelderman, MD, CEO of Monterey Medical Solutions

How it began: In today’s hospitals, medical professionals have access to a variety of tools that provide instant readings of a patient’s vital parameters. But in the 1970s, doctors could track blood flow through the hearts of critically ill patients only on an intermittent basis. In the mid- to late 1970s, Yelderman, then an assistant professor of anesthesia, began work on a device to allow continuous readings of cardiac blood flow.

What it does: The continuous cardiac output monitor uses changes in blood temperature as an indicator of blood flow through the heart.

Impact on medical science: Yelderman’s invention gave physicians the first real-time, continuous method of reliably assessing cardiac blood flow.

CyberKnife

Steve Gladfelter |

|

|

|

Inventor: John Adler, MD, professor of neurosurgery

How it began: Tumors that grow near the base of the skull and along the spine are a quandary for doctors. Surgical removal of such tumors, although effective, poses substantial risk of damaging vital nerves or arteries. In the early 1990s, Adler led a team that invented the CyberKnife, an image-guided radiosurgical instrument that eradicates tumors without incisions.

What it does: After a surgeon has precisely mapped the tumor on CT or MRI scans, the CyberKnife pinpoints hundreds of pencil beams of radiation through the target region. This approach is also more patient-friendly than conventional brain targeting techniques because it involves no metal frames or other immobilizing restraints that are screwed into the skull.

Impact on medical science: Since 2001, CyberKnife has been used on more than 25,000 patients worldwide. “It is revolutionizing surgery and radiotherapy — not only for brain lesions, but also for other areas of the body, including prostate, lung and pancreas,” says neurosurgeon Larry Shuer, MD, chief of staff at Stanford Hospital.

Pulse oximeter

Inventor: Bill New, MD, PhD, MBA, chairman of The Novent Group

How it began: As an assistant professor of anesthesia at Stanford in the 1970s, New wanted to reduce patient mortality and morbidity during surgery. He believed that problems with respiration were the primary culprit and wanted to find a way to instantly and continuously monitor a surgical patient’s respiratory condition. At that time, the process involved drawing and sending a blood sample to the lab for analysis, which usually took 15 minutes.

Steve Gladfelter |

|

|

|

What it does: The pulse oximeter is a noninvasive method of monitoring blood flow and the level of oxygenation through the use of light-emitting diodes, photocells and a simple microprocessor. The oximeter is usually clipped on the fingertip but can also be used at the nasal septum, ears, lips or tongue.

Impact on medical science: Pulse oximeters are now used in over 90 percent of operating rooms to monitor oxygen and perfusion levels in anesthetized patients, and have dramatically reduced the number of deaths associated with anesthesia.

Injectable collagen

Steve Gladfelter |

|

|

|

Inventor: Rodney Perkins, MD, chairman and chief medical officer of Sound ID

How it began: In 1974, Perkins, then a Stanford ear surgeon, was working with a medical student to create a synthetic eardrum out of collagen, the body’s main connective tissue protein. They joined forces with Stanford physicians Terry Knapp, MD, and John Daniels, MD, who were mincing up an inner layer of skin, known as dermis, and injecting it to fill wrinkles and solve other cosmetic surgery problems.

What it does: Injectable collagen is used to treat certain types of wrinkles and minor skin depressions. It can be used to fill acne and other scars on the face and to fill wrinkles on the forehead, cheeks and lips. Originally made from highly purified material from cow skin, most collagen now used in medicine is produced from DNA in a laboratory.

Impact on medical science: In addition to cosmetic surgery applications, collagen has subsequently been used to develop a synthetic eardrum, the initial problem Perkins sought to address.

Microarrays

Inventor: Pat Brown, MD, PhD, professor of biochemistry (co-inventor Dari Shalon, PhD, investor in Shalon Ventures)

Steve Gladfelter |

|

|

|

How it began: Studying genes one at a time was laborious, time-consuming and didn’t show how they interacted. In 1995, Brown led a team that created a fast, automated way of capturing gene interactions.

What it does: A DNA microarray, also known as a gene chip, is a tool used to analyze the activity of thousands of genes in a cell at once. It consists of a piece of glass the size of a microscope slide with an arrangement of spots of DNA strands attached to its surface. When the microarray is doused with a test sample, DNA strands from the sample stick to matching strands in the spots, creating a snapshot of which genes in the sample are active.

Impact on medical science: Microarrays have transformed the field of genetics by allowing researchers to do in days or months what previously would have taken years. “There is not a single field in the biological sciences that has not been touched by microarrays,” says Joseph DeRisi, PhD, who was a graduate student in Brown’s lab and is now on the faculty at UCSF.

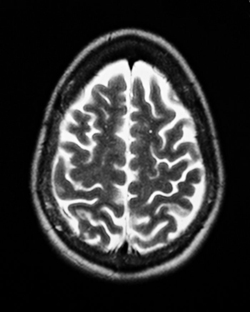

Nuclear magnetic resonance, the foundation for MRI

|

|

Inventor: Felix Bloch, PhD, deceased (former professor of physics)

How it began: In 1952, Bloch shared the Nobel Prize in Physics for the discovery of nuclear magnetic resonance, a phenomenon in which magnetic fields and radio waves cause atoms to give off tiny radio signals. NMR became a key spectroscopic technique in chemistry and biology. In the 1970s, researchers throughout the world began harnessing the power of this technique for medical imaging and in vivo spectroscopy.

What it does: MRI uses radiofrequency waves and a strong magnetic field to provide clear, detailed pictures of internal organs and tissues.

Impact on medical science: MRI is widely considered the greatest advance in medical imaging since the discovery of X-rays because of its ability to safely provide unparalleled views inside the body. Worldwide, more than 60 million investigations with MRI are performed each year.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorter

Steve Fisch |

|

|

|

Inventor: Leonard Herzenberg, PhD, emeritus professor of genetics

How it began: In the 1960s, no automated method existed to sort living cells according to their protein fingerprints. Herzenberg learned of a particle-sorting machine built by Los Alamos National Laboratory scientists to analyze the lung contents of animals exposed to nuclear test fallout. In 1969, he adapted it to sort live fluorescent cells.

What it does: The FACS sorts cells according to fluorescent tags bound to their surfaces. Because researchers can design the tags so they attach to proteins found only on certain cell types, the sorter can snare rare immune stem cells or identify cell populations that are waxing and waning in such diseases as cancer or HIV.

Impact on medical science: The FACS jump-started the fields of modern immunology, stem cell research and proteomics, and contributed to development of treatments for cancer, AIDS and other diseases. “So many experiments in modern immunology are possible only because of the FACS,” says Nobel laureate David Baltimore. Herzenberg received a 2006 Kyoto Prize for the cell sorter.

Phased-array ultrasound imaging

Albert Macovski |

|

|

|

Inventor: Albert Macovski, PhD, emeritus professor of electrical engineering and of radiology

How it began: In 1972, Macovski accepted a joint appointment at Stanford where he began to work on the whole spectrum of medical imaging systems, including X-ray, ultrasound, computerized axial tomography and MRI. His refinements gave these systems unprecedented subtlety and reliability.

What it does: In 1974, Macovski invented a way to dynamically focus sound waves and also steer them through space, resulting in sharper images. He accomplished this by building a new type of transducer to beam out sound waves. Instead of relying on just one quartz crystal to emit the sound waves, the new transducer used multiple quartz crystals arranged in circular and linear arrays. The transducer also made it possible to adjust the timing of the crystals’ pulses.

Impact on medical science: The phased-array ultrasound for the first time enabled doctors to observe not just the outlines but also the functioning organs of even a very young fetus.

Over-the-wire angioplasty

Inventor: John Simpson, MD, PhD, founder and CEO of FoxHollow Technologies Inc. (co-inventor Ned Roberts, MD)

Steve Gladfelter |

|

|

|

How it began: As a clinical fellow at Stanford in the early 1980s, Simpson attended a lecture by Andreas Gruentzig, a German radiologist who invented the balloon catheter to treat arteries clogged with plaque in a procedure called percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. PTCA used a balloon catheter, a long skinny plastic tube with a deflated balloon on the end, but the device was difficult for many surgeons to operate. So Simpson experimented with ways to make the system easier to use.

What it does: In over-the-wire angioplasty, a separate guide wire is used to position the balloon catheter. Once the catheter is passed through to the blocked area of an artery, the balloon is inflated to compress the plaque against the blood vessel wall.

Impact on medical science: More than 1 million angioplasties are performed worldwide each year, with success rates of 96 to 99 percent. The guide-wire innovation turned out to be one of the keys for improving both safety and outcomes of the angioplasty procedure.

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at