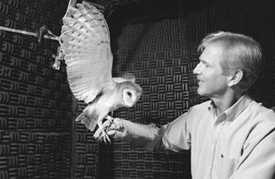

Photo: L.A. Cicero |

|

|

|

By AMY ADAMS

Toys that beep, crinkle, look interesting or require poking can leave a permanent imprint on a child’s brain, according to a Stanford study in owls showing that early learning experiences forever change the brain’s structure.

“This work shows the importance of investing in childhood experiences,” says study leader Eric Knudsen, PhD, the Edward C. and Amy H. Sewall Professor and the chair of neurobiology.

Knudsen’s previous research showed that young owls could quickly

pick up new skills that leave older owls baffled. What’s more, once

the young owls learn a new skill they can easily pick it back up as an

adult.

His new study, published in December in Nature Neuroscience,

focuses on a region of the owl’s brain that creates a spatial map

out of the sounds an owl hears, such as the squeaking of a mouse. The

owl then uses that map to know precisely where to hunt for dinner.

Knudsen and graduate student Brie Linkenhoker put glasses on the owls that shift the world to one side. When the owl first peers through the new specs, a squeaking mouse located off to the side appears to be straight ahead. This confuses the owl and allows its prey to escape.

The hungry owl solves this problem by learning a new auditory map that matches the shifted visual map. Without their glasses, the owls shift back to the original map. But later, after the human equivalent of many years, those owls can re-adjust to the glasses they wore as juveniles.

Mind-altering experiences

The research team wondered how educated animals held on to their learning. They thought that the neurons might make new connections that remained intact in adult animals. They turned out to be right. Neurons in the mapping part of the brain form connections with a group of neurons in the brain region that links those noises with the visual world. Adult owls that used the glasses as youths had both the normal and the shifted connections. Those extra connections enabled the animals to easily relearn to hunt with the glasses.

This work shows that the brain regions that help sense and interpret the world are most affected by early childhood experiences. “These have a huge impact on higher functions in later life,” Knudsen says.

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at