Short take

Babies with failing hearts get to grow up after all

Illustration: Juliette

Borda |

|

|

|

By RUTHANN RICHTER

Camila Gonzalez, the toddler with two hearts beating in her chest, grinned as she got off the van at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital, clapped her hands and told the driver, “Bravo!” It was a surprisingly cheery greeting for a child who just a few months before had cried and fussed at every hospital visit as she struggled through life with a heart about to give way to intensely high internal pressures.

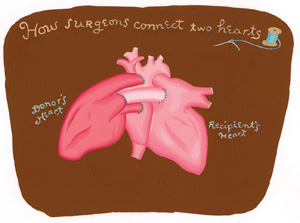

What transformed Camila, both physically and emotionally, was a rare surgical approach known as heterotopic transplantation. On Sept. 16, cardiovascular surgeon Bruce Reitz, MD, implanted a new heart alongside her own to help improve the heart’s output and lower the blood pressure in her lungs. She is the youngest child in the country to benefit from the procedure.

“When I told my husband about the surgery, he said to me, ‘Your doctor is crazy,’ ” recalls Camila’s mother, Maria Gonzalez. But now that Camila is recovering so nicely, she says, “My daughter has a second chance at life.”

Camila is the latest high-profile patient to emerge from the hospital’s Children’s Heart Center. Eight weeks before her operation, 5-month-old Miles Coulson also became a pioneer of sorts. Miles, his heart failing, was the youngest child — and one of only four in the country — to have a device implanted known as the Berlin Heart, which kept his blood flowing until a new organ could be found.

Miles had been so ill that his parents, Adrian Coulson and Leigh Bills, had said tear-filled goodbyes to him several times. As a last resort, his doctors turned to the German heart pump to resuscitate Miles until he could receive a transplant. The diaphragm-shaped polyurethane pump, which required special FDA approval to be brought into the country, sustained Miles for more than seven weeks.

“I thought, if this is his only shot, then give it a shot,” Miles’ father says of the agonizing decision on whether to try this largely untested technology.

Miles’ and Camila’s surgeries are examples of the hospital’s aggressive approach toward treatment, capitalizing on new technologies and surgeries to heal the hearts of young children who would otherwise die. Both babies benefited from the hospital’s 2 1/2-year-old pediatric heart failure program, one of the first in the country. According to the program’s director, associate professor of pediatrics David Rosenthal, MD, the goal is to intervene early before a child’s problem is so far along that nothing can be done. The program has mushroomed from two patients a week to about a dozen now, says Dan Bernstein, MD, the hospital’s chief of cardiology, co-director of the Children’s Heart Center and a professor of pediatrics.

“These are children who would have been referred back to a pediatric cardiologist in their community and would have deteriorated and died,” says Rosenthal.

The birth of the program coincided with the recruitment of two world-famous pediatric cardiac surgeons — Frank Hanley and Mohan Reddy — who brought with them a vast network of patients. Using Stanford as a base, they now direct a group of seven surgeons at medical centers in Oakland, Fresno, Sacramento and Honolulu where they perform about 1,100 procedures a year.

Parents at the heart

With these new strategies for treating ailing children, parents are sometimes put in the unsolicited — and often overwhelming — role of being medical pioneers making life-and-death decisions for their youngsters. So it was for Camila’s mother, who gave up her job and moved to Palo Alto from South Lake Tahoe to be with her ailing baby. Her husband, Salvador Gonzalez, a cook at Harrah’s Casino, stayed behind to provide family income and take care of their 12-year-old son.

Camila’s congenital condition, called restrictive cardiomyopathy, was far advanced by the time she first came to the children’s hospital as an outpatient on March 26. The left side of her heart had stiffened and was unable to fill with blood, raising the blood pressure in her lungs and putting enormous strain on the right side of the heart, which was greatly enlarged. The pressure in her lungs was five to six times normal, “about as high as you can get and still be alive,” says Rosenthal, who immediately admitted her to intensive care. She was, he recalled, “scrawny, poorly nourished and low on energy.”

After trying unsuccessfully to use drugs to treat her condition, doctors realized she needed a new heart. But a donor heart would never survive in such a high-pressure environment. So the decision was made to keep Camila’s existing heart and stitch it to a new one — aorta to aorta, ventricle to ventricle — so the two organs could work in concert while beating at their own individual pace.

Illustration: Juliette

Borda |

|

|

|

Decision time

When the idea was first proposed, Camila’s mother, who had worked as a nurse in a hospital in Mexico, came with a list of 20 questions. Would the two hearts ever beat as one? Would it still be possible for Camila to reject the new heart?

Even more to the point: “Are you going to practice on my baby?” she asked, knowing it was the first time Reitz had done the procedure on a child. The surgery had only been done eight times before in children in the United States; Reitz had applied the technique once in an adult in 1987.

“The doctors told me that without a transplant, she would live only two more years,” Maria Gonzalez says. “So we made the decision to have the heart transplant to save her life.”

It was an emotional process, too, for Miles’ parents, who learned two weeks into Miles’ life that his heart was giving out, mostly likely because of a viral infection. Miles, who was born in Dixon, Calif., near Sacramento, revived temporarily at another hospital with the use of an artificial heart-lung machine, but by the time he arrived by helicopter at the children’s hospital in June, he was critically ill. The doctors discussed the limited options with his parents.

“There were times when I felt that if Miles passed, that would be the best thing because he was suffering,” recalls his mother, who took a leave from her emergency services job to be at the hospital. “Some days I felt 100 percent that was the right thing to do. Other days I felt differently. I began to realize that I would regret it if we didn’t try something.”

The “something” turned out to be a device never used before at the children’s hospital, a German heart pump that had been implanted in 50 to 100 children outside the United States. It had been used in three other children in the United States, but all were much older than Miles. Two of those children survived; one did not. Reitz and his colleague, Robert Robbins, MD, while experienced with other support devices, had never implanted this one before.

The pump literally brought Miles back to life. He had been gray and cold before surgery; he emerged pink and healthy-looking. For the first time in months, he seemed happy, alert and relatively pain-free, as the pump collected blood through a small tube from one side of his ailing heart and sent it back through another tube into the body via the aorta. The pump was only a temporary fix, however. Miles needed a new heart. Fortunately seven weeks later, on Sept. 4, 2004, he got one.

Once out of the hospital, Miles lived in a temporary home in downtown Palo Alto, where he liked to watch “Baby Mozart” videos with his 2-year-old brother and ride in the stroller. He had to learn again how to eat (he was fed through a tube for months) and to speak (his vocal chords had been weakened by so much time on the respirator). He began to master simple movements, like grabbing his foot and shaking a rattle. He was back at home in time for Christmas.

Miles’ experience has opened the door for other children with heart failure so that they too might live with the help of this new technology.

###

Breathing easy

An unusual surgery creates a missing route to the lungs

Jenna Riley, 7, was born without a pulmonary artery and has struggled for breath for much of her young life. She survived with a patchwork of smaller vessels that made a circuitous pathway from her heart to her lungs, providing very little blood to fuel her body. Her legs were purple and her fingers blue and puffy; she spent much of her time in a wheelchair, says her mother, Melissa Riley.

A cardiac specialist near Jacksonville, Fla., where Jenna and her family now live, had told the parents that surgery was not an option. But as Jenna’s condition deteriorated, they began writing to pediatric cardiac surgeons around the country to see if one would take on Jenna’s case. Frank Hanley, MD, was the only one who agreed.

Hanley, director of the Children’s Heart Center at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital, fashioned a new pulmonary artery for Jenna in a 10 1/2-hour procedure on Oct. 6, 2004. He gathered in the smaller vessels, like the branches of a tree, to create a single trunk that replicates the function of this vital artery, he says. He also installed a donated human pulmonary valve. Jenna left the hospital 10 days later and is home doing very well.

“We never knew she had an olive complexion because she was so blue and purple,” her mother says. “It’s like a different child. It’s life-changing. She can run and walk and do all kinds of things… . He worked a miracle.”

Over the last decade, Hanley developed the operation that helped Jenna.

He now does about 75 a year on children from around the world whose pulmonary

arteries are not properly formed. “A lot of the big centers like

Packard are often considered the court of last resort,” he says.

“The families will turn to an institution like this because without

it, nothing can be done.”

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at