Jimmy Breslin writes about his brain surgery. His account in Mandarin coming soon?

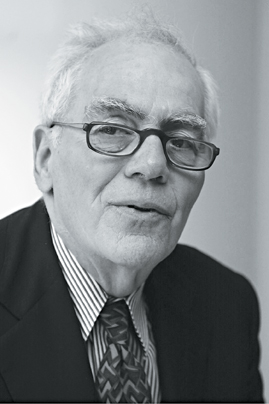

Newsday photo:

Alan Raia |

|

|

|

Jimmy Breslin won the Pulitzer Prize for Distinguished Commentary in 1986. His columns have appeared in various New York City newspapers and have been syndicated nationwide. He is the author of I Want to Thank My Brain for Remembering Me and several bestselling books, among them the novel The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight. He lives in New York City and had surgery for an aneurysm in 1994. His wife, Ronnie Eldridge, has been in public service most of her life. She served on the New York City Council from 1989 to 2001.

By JIMMY BRESLIN

The brain is the pennant winner of operations. Let these people sit around and talk of their grubby kidney removals, prostates, hip replacements and even open heart surgery. Mention a brain operation and all in the room shrink to the wall.

“Show them,” my wife says.

The people sway away.

“See?” she says. She grabs my hair and tells them to look.

“You won’t believe this. They cut him from the top of one ear right across the front and he doesn’t even have a scar.”

This is about an aneurysm operation. It is a very important account because it happened to me.

This all started when I had a headache and my left eye shut. “Freaking blood sugar,” I muttered. I went around to the eye doctor, Robert Newhouse, and his prescription read, “MRI — for possible aneurysm.” Pretty good first look. I didn’t know what an aneurysm was, but I sure had seen the word in obituaries. So I took the test.

In the machine, I felt like I was visiting an old friend. The MRI won a Nobel Prize for I.I. Rabi, the physicist who was one of my favorite New Yorkers. On the day I won a Pulitzer Prize, he came flying downtown and hopped up on a barstool that was so rickety we had to keep a hand on it all day. He aroused the reporters when he told them, “It is a fact that we have free speech in this country. But everyone is afraid to use it.”

Now, after the MRI test, the doctor said it looked all right. Two days later, the phone rang and his secretary asked me to hold on. There was flashing. Her voice came on again. “Hold on.” I said to myself, this is exactly how they tell you in stories about hearing bad news. Suddenly, the neurologist came on. “Your eye is fine but apparently, you have an aneurysm in front.”

“In front of what?” I asked.

“The front of the brain.”

“How do they treat that?” I asked.

“With a brain operation.”

My wife, who was an elected New York City politician, started to ask surgeons for their best choice for me. She kept a chart, the way she would for delegates to a convention. Twenty out of 21 gave the name of Robert Spetzler of the Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix.

So I went to Phoenix. I was standing at the window in the hospital room and looking out at a lone streetlight burning on the empty street in the night.

I watched a car go by. I was supposed to be beside myself with nerves and outright fear. Instead I was calm and sleepy. I was in the state of grace. Because of all the stories for newspapers that I wrote about the poor and the blacks. Doing anything to help them is the sure way to salvation. And right then, they were saving me. I thought, I’m going to have my head opened and I have no nerves. I am going to sleep.

Earlier, we had come off the plane and gone right away to see the surgeon. He said, “What do you do for a living?”

My wife leaped off the chair. “He has a Pulitzer Prize!”

We have never uttered a word about the thing but right now she was terrified that the man wouldn’t take prize-winning care to protect my living.

Already, a surgeon, a friend, Daniel Coit at Sloan Kettering, told me, “You might come out improved.”

It was such a beautiful thought that I clutched it that night. I was also thinking about the guy down the hall who had a head injury that had bashed the nouns out of him. The only thing he could say was “taxicab.” They held up a jacket and he said, “taxicab.” They showed him the luncheon plate and he said, “taxicab.”

I looked out the window and tried sentences with only one noun. If it only could be “they,” I thought, so I wouldn’t have to worry about gender. At least I could say, “They reported the shooting.” Or, “They reported the attack.” Then I could sit and wait for the detective to type up the report. I could take it and copy it in my story. The trouble was, I knew mainly older detectives and they can’t type. I’d have to sit around for hours for one report.

After considering all this, I fell into bed and slept until morning. My family came in and we held hands with a priest and said prayers. My family went to the waiting room. The priest went out and molested some small boy and got into a lot of trouble. I’m not kidding. They wheeled me into the operating room.

“I could use some coffee,” I said, on the way.

“You can’t have anything if you’re having brain surgery,” the nurse said.

DOCUMENT 39303311/22/94

OPERATIVE PROCEDURE. Right frontal temporal craniotomy clipping of anterior communicating artery, unruptured aneurysm with placement of a small cotton ball around the unclipped portion.

And on it goes. There are long paragraphs of description dictated by Spetzler, but as I am writing this for a big university medical school publication, I expect most of the readers to know all about this.

In starting inside my head, Spetzler saw the optic nerve, white, pearly. Touch the nerve and I promptly go blind. Right now it is very good to have a genius with hands that can work on tiny vessels that govern life and death. The aneurysm had two lobes and a nubbin. The blood swirled around the inside of the aneurysm’s thin, almost transparent lobes. It was a bomb that could go off without ticking. He worked two and a half hours, then clipped them with a titanium clip that looked like a small tie clasp.

There was a piece of white skull left over from the drilling that started the day. He took the piece and fitted it into the skull like a brick. Two miniature hinges were put into the skull by a resident using a screwdriver. If they have to go back someday, they can just open the skull like a front gate.

The next day Spetzler came in and asked me to tell him my name. I had been rehearsing this for days.

“J.B. Number One.”

He asked me what city I was in.

“Topeka.”

Outside, my wife said, “He was like that when he got here.”

I got back to the hotel a couple of days later. The first thing I did was sit down and write what I thought was a column about my brain operation. It shocked me. The whole first page read like oatmeal. I didn’t lose just nouns. I lost the whole thing. Then Dan Coit’s opinion that I could be better than before ran through me. If I know this is so bad, I told myself, then I know how to fix it. I sat down the next two days and carefully wrote a column. What really helped were the hours after the first day when I swam in the pool and thought only of the piece. I knew the sentences and ran over them while I swam. You call this homework. In the morning, I went right through it. The paper ran it prominently.

“I’m big!” I told myself.

After that, when people asked me how I was, I answered, “Big!” And then “very great.”

And we come to the night that proved the enormous power of having a brain operation on the resume. I am at a dinner party in rich Westchester County and people kept asking me how I felt and at one point there was a network news president, a newspaper editor, a stockbroker and a couple of others and I said, “The strange thing is that when the guy went in there I guess he touched a couple of wires. But I woke up able to do physics. I never even could do long division. And I began talking Mandarin. Not a lot, but enough to make myself known.”

“Had you studied any of that before?” one asked me.

“Nothing. But a doctor in Manhattan, Dan Coit, told me this could happen. I have all these abilities hidden in some chamber of my brain and they just had to be jogged to come out. I think I am going to keep up with the Mandarin.”

Not one of them didn’t believe me. They stared in wonderment. And I sat down to dinner and had them all on the defensive. I looked around and said to myself, “Good boy yourself, Breslin. JB Big.”

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at