The science and ethics of exploring the mind

Gérard

Dubois |

|

|

|

![]() SIDEBAR

1: The meaning of dreams

SIDEBAR

1: The meaning of dreams

![]() SIDEBAR 2: Stanford's

neuroscience institute

SIDEBAR 2: Stanford's

neuroscience institute

![]() SIDEBAR

3: Neural play-by-play

SIDEBAR

3: Neural play-by-play

By AMY ADAMS

The most human of qualities is the capacity for romantic love. It has stirred bards, inspired wars and is one benefit of a mind that can think and feel. So, it is somewhat humbling that neuroscientists can now pinpoint exactly which nerves fire up when a person views a picture of his or her beloved.

Turns out it was just a few twitchy brain cells that launched the thousand ships.

If that’s the case, where does that leave other human qualities such as creativity, curiosity or consciousness? Given experiments already under way, we may soon be able to locate where in our brain these most cherished personality traits reside. Scientists are even learning new ways to change the brain that could fine-tune moods and feelings with greater precision than the latest drugs or therapies allow. That’s more than just a little unnerving.

Back in 2001 Judy Illes, PhD, began noticing more of this unsettling research on what makes us us — and how our very nature can be altered. She was delving into how researchers should handle the new kinds of information about our brains and our selves with the intention of sparking a new area of activity for Stanford’s Brain Research Center, which she had co-founded.

Instead, Illes’ work catapulted her across campus into the Center for Biomedical Ethics, where she is now a senior research scholar and directs the center’s program in the budding field of neuroethics. She and other scholars are identifying and beginning to answer many of the ethical questions surrounding how researchers, policy-makers and the public should handle new information about the function of our brains.

One of the discipline’s founders, Illes co-hosted the seminal meeting in 2002. Pulling together ethicists, neurologists, philosophers and religious leaders from institutions across the United States, this meeting helped set the agenda for the field. Now, the founding neuroethics centers at University of Pennsylvania and Stanford are joined by colleagues at Johns Hopkins, UC-San Diego, Dartmouth, Harvard, Columbia, University of Alaska, University of Alabama and the Karolinska Institute. Together, their goal is to get a head start on thinking about how new brain research should be carried out and applied in the years ahead.

Looking within

At the forefront of brain-imaging research are technologies that reveal which brain cells are active during given activities. One technology in particular, functional MRI, has had a starring role in delving into the workings of the brain and mind.

The method is a modified version of a technique called MRI, or magnetic resonance imaging, which measures how molecules in the brain line up when placed in a magnetic field. A person slides into a massive tube containing a powerful magnet. When turned on, the magnet is strong enough to erase credit cards, pull at earrings or tug the brain’s molecules into alignment. A snapshot of the brain molecules reveals the brain’s convoluted folds. These MRI images remain remarkably consistent among different people.

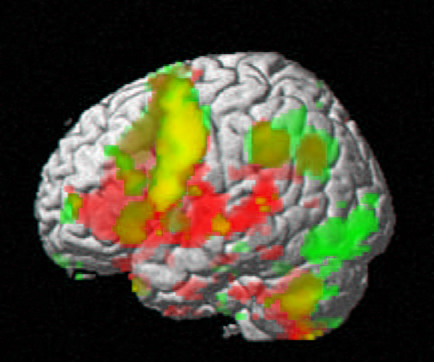

Where individuals differ is in which brain cells respond to humor, anger, stress or the sight of a loved one. It’s these intimate details that functional MRI, better known as fMRI, reveals. Rather than detecting the brain’s density, fMRI records which part of the brain has greater changes in blood flow during a particular task. This is an indirect measure of which brain cells are active — and therefore require extra blood supply — at that moment.

If blood rushes to a particular region when a person tries to speak, then that region is likely to be important for forming words. This type of basic brain function tends to be hard wired. All of us seem to use similar parts of our brains for basic tasks such as processing images and sounds or forming words. Knowing the brain’s functional layout helps determine, for example, if surgery would remove parts of the brain too vital to live without. Likewise, it can help doctors predict the long-term prognosis for a person who has had a stroke.

Other studies look at aspects of our brain that are more ethereal, such as the seat of love, cravings or deceitfulness. This field, called cognitive neuroscience, began taking off once the power of fMRI dawned on researchers. Now cognitive studies account for a large majority of all published fMRI research. The question for cognitive neuroscientists is, what does it mean if blood rushes to different regions of the brain in people carrying out the same mental exercise, such as lying? Is one person more prone to deceit? That’s where the brain-imaging studies raise issues about the nature of our own personalities and provoke some tough questions.

According to Scott Atlas, MD, professor of radiology, who carried out an fMRI study looking at sexual response, it’s a bit early to know exactly what individual variations mean in this and other fMRI studies. In his work, 14 men watched sexually explicit videos while undergoing fMRIs. Later, complex software compiled a study average of which parts of the brain were most active while viewing the images. In this case, a handful of neuron clusters throughout the brain all lit up in sync.

Matthew Kirschen |

|

|

|

Although these regions fired frantically in all of the men as they watched the sexual images, each participant showed a slightly different pattern. That makes sense, given people’s individual tastes. In time researchers might be able to match brain-activity patterns with certain preferences. There might be a signature brain pattern for those who prefer blonds.

Atlas, who has collaborated with Illes, says it’s worth thinking about how researchers should deal with this type of personal information now, before it is possible to predict a person’s sexual orientation or preferences. What if, for example, researchers learned to recognize the signature brain pattern of a pedophile? Would they be obligated to tell the person what his or her brain revealed, or to inform the person’s employer or law enforcement?

More of a near-term concern for Illes is what study participants think they can learn about themselves, as illustrated by a tale she heard from her colleague Russell Fernald, PhD, the Benjamin Scott Crocker Professor of Human Biology. He says undergraduate students who participated in a brain-imaging study were later overheard at their dorm comparing the size of their amygdala — a brain region involved in anger and other emotions — without understanding what such differences might mean. “Communicating what the scans reveal and don’t reveal is imperative,” Illes says.

A related concern has to do with brain anomalies revealed by imaging studies. Illes, along with Gary Glover, PhD, professor of radiology, and MD/PhD student Matthew Kirschen have been leading an effort with the National Institutes of Health to improve how researchers present a study’s objectives to participants so it is clear what they can expect to be told if abnormalities do turn up. She adds that the Lucas Center, which houses Stanford’s imaging equipment and has put considerable effort into how participants are informed about a study and its goals, is a good model for how centers nationwide should handle the process.

Gérard Dubois |

|

|

|

The risks of fMRI research are accompanied by huge potential clinical benefits. Atlas is currently examining the brains of obese people and of people at a healthy weight as they both salivate over images of food. The researchers might find that obesity is all in a person’s head. Could obesity be seen as a brain disorder like depression or anxiety attacks? And would that alter how obesity is treated or viewed by society?

For now fMRI is still too expensive to screen every obese person even if such an overeating brain region turns up. But the work could help researchers understand the condition and perhaps lead to treatments, whether they are drug-related and targeted to certain parts of the brain, or simply change how obese people view and react to food.

That’s where the brain differs markedly from organs such as the liver or kidney — it can be talked into and out of responses. Changing how a person thinks about food is a conceivable treatment for a medical condition. In fact, a recent study from UC-Irvine found that people could be convinced that they dislike strawberry ice cream or love asparagus simply by the power of suggestion. That’s because a person’s mind can be stronger than the brain, even though the former exists within the latter. Nothing illustrates this flexibility better than studies of depression.

People with clinical depression have a group of interconnected brain regions that fail to communicate properly. This organ failure is responsible for the sense of hopelessness, fatigue and inability to cope that are the outward hallmarks of depression. What was once thought of as a problem of the mind is now increasingly dealt with strictly as a biological problem, with medication, like high blood pressure or heartburn.

But according to Brent Solvason, MD, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, talking about the reasons for depression can be as effective as medications such as Prozac or Zoloft — known as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Therapy, he says, can knock the misfiring neurons back into gear. That’s like treating high blood pressure by giving your arteries a good talking to.

“If you believe the TV commercials, depression is caused by these serotonin molecules that don’t remain long enough in the neuron synapses,” he says. But if that were all there is to it, why, as many psychologists and patients say, does talk therapy work so well? And why do some drugs that speed serotonin reuptake also treat the disease? Solvason says that all of these jar the network of neurons and reset them to a normal mode, like kicking a vending machine to get a candy bar out. A kick to the front of the machine or a little jiggle on either side can all work to dislodge the treat.

Essentially, the mind is able to kick the brain back into working order.

“That’s one of the wonderful and mysterious things about the brain,” says Karl Deisseroth, MD, PhD, assistant professor of bioengineering and of psychiatry and behavioral sciences. “All these thoughts and emotions are electrical patterns flowing through the brain in specific ways.” He says talking about memories stimulates electrical activity in the brain. “Those patterns do real things and can cause lasting changes to the brain.”

Deisseroth and Solvason are now collaborating on a study for treating depression that raises additional neuroethical concerns. It turns out that electroconvulsive therapy, also known as electric shock, remains one of the most effective treatments for depression and some other mental illness. But the side effects (including sleep disturbance, memory problems and altered libido) make the treatment a last resort. So the two researchers are studying a new, still-experimental technique called transcranial magnetic stimulation, or TMS, which might hold the benefits of electroconvulsive therapy without those serious side effects.

In TMS, a hand-sized magnet generates an electrical current that can be directed to regions at the brain’s surface. A quick jolt to the depression network seems to be one additional way of smacking the vending machine. “TMS really could be the future of brain interventions,” Deisseroth says.

Whereas drugs shake up all the neurons in the brain, TMS delivers a more targeted jab to brain regions about the width of a pinkie finger. So far, the study by Stanford researchers and colleagues at other institutions hasn’t produced any final results, but the group hopes to find out how well TMS works by the end of 2005. If it’s successful, Solvason says it could be used to help people with a variety of mental illnesses.

Rejiggering the brain

The combination of fMRI to identify misfiring brain regions and TMS to realign them opens a new era for neuroscience research — one that Illes has her eye on. It’s one thing to find parts of the brain that are different in people with some illnesses. Like genetic testing, this information can help predict diseases that might occur in the future. It’s quite another thing to jiggle that disruption back into normality. “Fortunately we aren’t there yet,” says Fumiko Maeda, MD, PhD, a research associate in psychiatry and behavioral sciences. “We will have to work in tandem with neuroethicists and take it very carefully.”

Illes says she does not object to treating mental disorders with these new technologies. She’s all for that. But she says tinkering with the brain shouldn’t be taken on lightly. “We certainly mustn’t slow down research,” Illes says, “but we should think in advance about what issues might come up.”

Many of the issues Illes has pondered about TMS are similar to those she and others have discussed about the widespread use of SSRI drugs. Among them, nobody knows the long-term effects of artificially altering networks in the brain.

“Because these methods touch on the human mind we have to think about them proactively,” Illes says. If TMS does turn out to effectively treat depression or other disorders, Illes says it will be helpful to have considered the potential negative repercussions in advance. “By identifying questions now we can ensure safety and responsibility down the road,” she says. This forward thinking could alter how researchers explain the treatment to patients or encourage patients to ask more about proposed therapies.

Along those lines, another question is whether a person should be pre-emptively treated for a disorder that appears on fMRI, such as addiction or aggression. This is where the thinking of Illes finds common ground with the work done on ethical issues in genetic testing. If a test reveals a predisposition to either a disease or a mental state, what should be done with that information? If insurance paid for the test, should that predisposition show up on a person’s medical record? And can a person be required to deal with a potential anger management problem or an as-of-yet unrealized predisposition to depression or addiction? Much of this comes down to carefully explaining the issues to people before they participate in a study or pay for a private medical test that would reveal such personal information.

What makes such decisions so difficult to contemplate, according to Atlas, is that scientists are still struggling with what an abnormality on an fMRI scan even means. “Complex processes are probably quite variable,” Atlas says. So for something complicated, like mood, most people might veer slightly from the statistical average. “The data are not as clinically useful if they’re limited to comparing groups of people,” Atlas says. Until researchers can correlate an individual scan with an individual person’s risk of disorders, fMRI remains primarily a way of mapping out general regions of brain function rather than an effective way of diagnosing disease.

Whether fMRI is used to diagnose disease in the near future, technologies to prod, zap and otherwise coerce brain regions into compliance are just waiting for new brain regions to explore. A technique called deep brain stimulation, in which a battery pack embedded in the chest powers a wire leading to regions deep in the brain is already being used to calm tremors in Parkinson’s disease. Jamie Henderson, MD, assistant professor of neurosurgery, is considering starting a trial using DBS to treat depression or obsessive compulsive disorder. And chronic pain patients have been having success controlling their pain through biofeedback using real-time fMRI images that show them their brain when they’re in pain and when they “think” the pain away.

As this work progresses it could be that aspects of our personality that we once considered profoundly our own can be tweaked and reshaped like so many plucked eyebrows. If that day comes, Illes and her neuroethics team are working to ensure that scientists, policy-makers and the public are prepared to deal with the implications of this mental tinkering.

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at