Researchers catch stem cells in the act

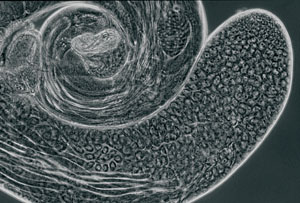

Photo: Leanne Jones,

PhD |

|

|

|

A fruit fly's testis. Stem cells form at the tip and create cells that mature into sperm. |

|

By AMY ADAMS

Stem cells, though widely studied for their disease-treating potential, are still a bit of an enigma. For most tissues, nobody knows precisely where the cells live or what their environment normally looks like. Studying them under laboratory research conditions is akin to studying animals at the zoo without ever having seen their natural habitat.

One of the few places to see stem cells in the wild is the testis of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. Stem cells at the tip of the elongated testes repeatedly divide to produce one cell that will make sperm and another stem cell. By tweaking the environment of these cells, postdoctoral fellow Leanne Jones, PhD, working with developmental biology professor Margaret Fuller, PhD, has uncovered many of the proteins these cells use to communicate.

Jones says this work can help human stem cell researchers understand how their captive cells grow and divide. "The molecules will be different but the general principles may be the same," Jones says. She has already found some proteins that have parallels in human cells.

In the fly, a handful of stem cells surround a core group of cells called the hub, located at the furthest tip of the testes. These hub cells give a constant "you are a stem cell" signal. When the stem cell divides, one cell remains in contact with the hub and continues to receive the stem cell signal. The other cell, farther from the hub, doesn't get that signal. It loses its stem cell identity and develops into a cell that will make sperm.

To better understand how the hub communicates with the stem cells, Jones

has studied flies that make too much or too little of the stem-cell-inducing

signal. She finds that some of these flies produce way too few stem cells

and others produce too many -- and none makes normal amounts of sperm.

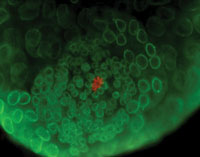

Photo: Leanne Jones,

PhD |

|

|

|

At the tip of the testis, a few cells form a hub (red). The hub controls which stem cells will become sperm. |

|

Work by researcher Yukiko Yamashita, PhD, fills in the picture, revealing that the orientation of the stem cell's plane of division determines the newly formed cells' futures. If she creates mutant flies in which the stem cell's plane of division is perpendicular to the hub – with each new cell touching the hub – rather than parallel, then both new cells become stem cells.

Fuller says all normal stem cells, whether they are in a fruit fly, mouse or human, have some way of regulating division so that one cell remains a stem cell and the other develops into a mature cell, be it a neuron, red blood cell or sperm. "The fly models have provided some paradigms that have helped people know what to look for," she says.

One of those paradigms is that the cell must be oriented correctly in relation to other cells when it divides. She says, based on this information, people hunting for the normal home of blood-forming stem cells in mice have started looking close to other cell populations. They think they may have found blood-forming stem cells living near immature bone cells in the bone marrow lining.

Finding stem cells in their natural environment within the bone marrow, brain, skin or other organs is like finding which tree a bird lives in and what bugs it eats. Researchers can use that information to manipulate the cell's behavior in a lab dish -- one step in the long-term goal of using stem cells to repair or replace damaged tissue in people.

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at