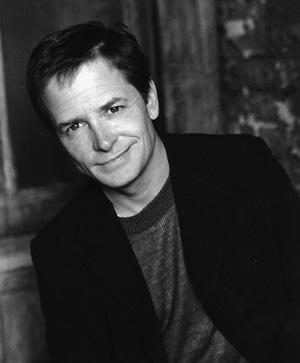

He's laughing at himself. But not at Parkinson's

Mark Seliger |

|

|

|

When it comes to Parkinson's disease, "the science is way ahead of the money," says Michael J. Fox. Though "just" an actor, Fox knows as much about the state of brain disease research as many neuroscientists. He makes it his business now that one of his major pursuits is finding a cure for Parkinson's.

Fox gained worldwide popularity in the 1980s with his role as Alex P. Keaton on NBC's "Family Ties." After this early success, he went on to star in the TV hit "Spin City" and in motion pictures, including the blockbuster "Back to the Future" trilogy, "The American President," "Bright Lights Big City" and the "Stuart Little" films, as the voice of the leading mouse.

Though Fox continues to perform occasionally, his priorities changed in 1991 when he was diagnosed with Parkinson's. It's a disease with no known cure. So he founded the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research, turning his energy to fundraising and grantmaking -- all aimed at beating the disease.

Fox lives in New York City with his wife, actress Tracy Pollan, and their four children: a son, age 15; twin daughters, 9; and a baby girl, who'll be 3 in November.

Michael J. Fox recently spoke with Stanford Medicine:

Do you get tired of people asking you, "How are you doing?"

Fox: No -- I understand that it comes from a genuine connection people feel they have with me. So many people tell me, "I grew up with you." Television is such an intimate medium that in a way, they did. So the concern and the connection are very real.

So. How are you doing?

Fox: Fine, thanks.

This past television season you played a surgeon with obsessive-compulsive disorder on NBC's "Scrubs." Was there any message there?

Fox: Not really. It's a funny show and Bill Lawrence, the producer, is a friend of mine. So when he asked me to do it, I said sure. The overall message of the show is a recognition that we're all human, with our individual flaws and foibles, which has an appeal to me. Everyone gets hit with their own bag of hammers at some point in life, you know. And it was just fun.

Telling your children that you have a chronic illness must be one of the most difficult discussions a parent ever faces. How do you strike a balance between sharing enough information and sharing too much?

Fox: I don't pre-package it for them. I tell the basics in an honest, open way and then let them be with it. What's important for them is not how I feel about having PD, but how they feel about my having PD. I give them reassurance, because I'm a classic optimist, not a fearful person, but it's their experience that matters. It really hasn't been a big thing -- they know they can ask me anything anytime -- we've got a lot of regular everyday family stuff going on.

Is anger a motivating force or a debilitating one?

Fox: I find it neutral and therefore a distraction. It's hard to avoid in the early going but I don't go there much anymore.

Having a chronic illness is pretty serious business. Do you find any humor there?

Fox: All the time. I take PD seriously but I rarely take myself seriously. That's the secret.

How has your illness influenced your view of health care in America?

Fox: It has made me much more aware of the tremendous financial burden that many people bear. I'm in a pretty privileged position where I don't have to worry about cost of medications, whether I can afford a particular therapy that might help me or whether it's covered by insurance. So many people aren't and have to deal with this financial aspect on top of the illness itself. It's a serious issue in this country.

What are some of the biggest misconceptions about Parkinson's?

Fox: That it is a disease that only affects your grandparents and so somehow is a part of aging. I've met so many people in their 30s, 40s and 50s -- baby boomers and younger, who have the disease. It affects their ability to be productive in their jobs, in their families, right at the prime of their lives.

Is there any one thing you would like everyone to know about the disease?

Fox: People should know that scientists say of all the neurodegenerative diseases, Parkinson's is closest to a cure in our lifetime. I firmly believe this to be true.

|

|

Why does progress in biomedical research matter to someone who lives with Parkinson's today?

Fox: It matters because we are so close. A focused and forceful effort can improve and/or save the lives of millions of people in the very near future.

Is there anything on the horizon as far as research breakthroughs that particularly excites you?

Fox: There's a lot in the pipeline. Our foundation, for example, is leading the search for the first biomarker, or diagnostic test. We thought this was a fishing expedition when we started a year ago -- but preliminary results are really exciting. We're also excited about the progress we see with naturally occurring growth factors -- the best known is called GDNF -- which appear to protect and rejuvenate the neurons that die in Parkinson's disease. We see breakthroughs in understanding the genetic risk profile of the disease: we're funding the creation of the first gene chip for PD. And of course, while we think cell replacement therapy is further away on the horizon than once thought, it still holds tremendous potential for a cure.

How important is stem cell research to the search for treatments and a cure for Parkinson's?

Fox: Stem cell research is a critical pathway to a cure in two ways. First, stem cells can be used for cell replacement therapy, to actually produce dopamine neurons that have been lost. There are still quite a few hurdles -- the brain is tricky and you'd need to go in without causing damage and figure out how to get the cells to thrive -- but it's tremendously promising. Aside from that, most people don't even focus on something that's perhaps even more important -- how critical stem cells are for research. You can't do research on living human neurons. But you can use stem cells to create them and study how they work and the impact of various drugs. It's huge.

Are you surprised about the intensity of the political debate on stem cell research?

Fox: It's nuts. Those of us with Parkinson's and other degenerative diseases see it as so self-defeating. We don't want to clone a Frankenstein or Uncle Charlie so we can play poker with him again. We just want to save lives.

Do you feel as though you are in a race against time?

Fox: So many people assume that I'm in this to cure me. While that would be great -- and don't get me wrong, having Parkinson's stinks -- that's not what this is about. It's like being trapped in a mine with a bunch of people. You don't think, when will I get out. You think, when will we get out. So in that sense, I am impatient. I want all of us to get out.

Besides hurry up and find a cure, is there any other message you would like to share with biomedical researchers?

Fox: We recognize that when it comes to Parkinson's disease, the science is way ahead of the money. That's why our foundation is trying to fill the void. So come to us with a "hit it out of the park" idea and if it passes muster, we'll look for a way to make it happen.

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at