Just what can adult stem cells do?

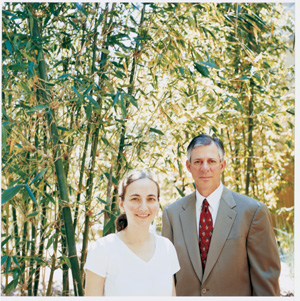

Photo:

Amanda Marsalis |

|

|

|

Leora Balsam and Robert Robbins. They injected adult stem cells into heart tissue to learn if the cells transform into heart muscle. |

|

By AMY ADAMS

People who survive a heart attack carry a permanent reminder of their ordeal. Where heart cells die from the lack of oxygen, scar tissue fills the gaps and leaves the heart weaker and less able to pump blood. Knowing this, Robert Robbins, MD, director of Stanford's Institute for Cardiovascular Medicine, took note when researchers from New York Medical College published a 2001 study showing that blood-forming stem cells from bone marrow had repaired damaged heart muscle in mice.

This was one of a growing number of studies claiming that injured tissues could be repaired by adult stem cells -- stem cells from tissues in mature humans or animals, as opposed to cells from embryos or fetuses. This paper appeared amid international debate over the therapeutic role of adult stem cells.

Everybody agrees that the adult cells can treat diseases within their own tissues -- blood-forming stem cells can replace bone marrow cells destroyed during cancer treatment, for example. What they can't agree on is whether adult blood-forming stem cells can repair other tissues such as the liver or heart muscle, as the New York Medical College team, led by cardiologist Piero Anversa, MD, reported. The stakes are particularly high in this debate given that one rationale for banning embryonic stem cell research rests on the idea that adult stem cells are just as versatile a tool for treating disease.

Rather than taking sides, Robbins decided to test whether the New York group's adult stem cell therapy might help his Stanford patients. As a first step, Robbins and research fellow Leora Balsam, MD, tried to reproduce the results in mice. Their work, published in a March 2004 Nature paper, added another twist in the discussion over what an adult stem cell is capable of.

Switching careers

The adult stem cells under debate are the newly minted college graduates of the cellular world -- they have a specialty but can still pick and choose what to do within that field. Blood-forming stem cells in the bone marrow, for example, are committed to creating blood cells, but they have a choice of generating red blood cells or any type of immune cell. Likewise, neuronal stem cells in the brain produce new neurons as well as the brain's support cells.

Other types of stem cells in the skin, muscle and other tissues keep their respective organs flush with new cells. Researchers at Stanford and across the country are trying to find adult stem cells for each tissue, hoping to use these cells to treat diseases in the host tissue or, in some cases, to repair cells in other tissues.

Most people studying the potential of adult stem cells use the well-characterized blood-forming stem cells found in the bone marrow. However, researchers differ in the methods they use to investigate these stem cells and in how promising they find the results of these experiments to be. Stanford's Irving Weissman, MD, (SM '65) and his colleagues isolate purified blood-forming stem cells and inject only that specific cell population back into mice. It's this purified cell method that Robbins and Balsam used at Stanford in their attempt to replicate Anversa's heart muscle work.

Many other researchers, including Anversa, have found that blood cells contribute to other tissues when less-purified batches of bone marrow cells are injected. These collections of cells include blood-forming stem cells in addition to many other types of blood and bone marrow cells. Weissman, who is also director of the Stanford Institute for Cancer/Stem Cell Biology and Medicine, argues that this approach makes it impossible to tell which cell within the bone marrow is the one that's later found in the heart, brain, liver or skeletal muscle.

Photo:

Helen Blau, PhD |

|

|

|

Evidence from Helen Blau's lab that the offspring of blood-forming stem cells can fuse and join forces with neurons. The cell is a purkinje neuron. Its green glow indicates that a blood cell's nucleus is making a protein active only in purkinje cells. |

|

Stanford molecular biologist Helen Blau, PhD, and her colleagues have done experiments using both whole bone marrow and purified blood-forming stem cell populations. Months after injecting either type of cells, they find normal brain and skeletal muscle cells that contain a green protein made only by the injected blood cells. In most cases, these fused cells also had at least two nuclei, one of which came from the blood cell.

Blau, who holds Stanford's Donald E. and Delia B. Baxter Professorship, says that when she injects batches of purified cells, the only ones that fuse are the immediate precursors of macrophage immune cells, called myeloid progenitors. Markus Grompe, MD, at the Oregon Health & Science University has found that these same cells fuse with diseased liver cells when injected into mice. Grompe has shown that the nucleus from the myeloid cell can reprogram itself to activate genes normally used only by the liver. Likewise, Blau has found that blood cells fused with neurons and that the blood cell nuclei began producing proteins normally made by highly branched neurons in the brain, called Purkinje cells.

"I think the fact that they can fuse is really exciting. We never even knew fusion occurred," Blau says. She had studied cell fusion products in a lab dish for many years, but never thought it happened in brain and muscle cells of living animals. Blau thinks pre-myeloid cells might be part of the body's rescue mechanism, traveling the bloodstream to shore up damaged tissue. If this is the case, they could be used therapeutically to deliver normal genes to tissues damaged by genetic diseases. Grompe showed this very thing, using mice with a condition that mimics a human liver disease. The fused blood cells delivered a healthy copy of the gene and cured the mice. Blau and her group are trying to use this same mechanism to treat muscular dystrophy and brain diseases such as stroke and Parkinson's disease.

In Weissman's experiments using purified blood-forming stem cells, he also sees blood cells fusing with cells of other tissues, but only as an extremely rare event. Still, he's in favor of finding adult stem cells from each tissue and using those to treat disease. He doubts that blood cells fuse often enough to effectively repair damaged tissue.

Although Weissman doesn't think blood cells are the best way to approach tissue repair, he feels the research could produce valuable information. "It's worth it to understand what happens with fusion because it's an important biological phenomenon," he says.

Weissman's the first to admit that if adult cells from one tissue could repair another tissue, he's poised to rake in the big bucks. He has started three companies developing therapies using adult stem cells in their own tissue of origin: neuronal stem cells to treat brain diseases and blood-forming stem cells to produce blood cells.

Photo:

Leora Balsm, MD |

|

|

|

The stem cells (green) failed to produce a protein typical of muscle cell (red), suggesting that the stem cells do not transform |

|

Embrace the differences

Robbins and Balsam's findings added a wrinkle to the debate over whether blood cells can incorporate into tissues and how effectively those cells repair damage. In collaboration with Weissman and postdoctoral scholar Amy Wagers, PhD, now an assistant professor at Harvard, they injected purified blood-forming stem cells or less pure bone marrow populations into mice with an induced heart attack. In contrast to Anversa's results, heart muscle did not regenerate.

"We're all interested in finding ways of regenerating the heart," Balsam says. "I think what this study points out is that it's not easy."

The blood-forming stem cells did lodge in the damaged heart muscle, but they didn't turn into muscle cells, didn't fuse with the existing cells, didn't help the mice live longer and didn't improve the heart's ability to pump blood. Instead, they maintained their blood cell characteristics while nestled in the damaged heart tissue.

Still, the stem cells lessened some of the heart attack's damage by minimizing the expansion of the heart's left ventricle. The question of why remains open but Balsam guesses that those blood cells wedged in the heart might recruit additional blood vessels to the area or otherwise support the remaining heart muscle cells.

Robbins says that if the blood-forming stem cells go to the heart muscle, as they appear to do, perhaps those cells could be engineered to produce therapeutic proteins that prevent inflammation or help preserve heart tissue that remains after a heart attack. Even if they don't fuse with the heart muscle or turn into new heart muscle cells, these blood cells could be of use in treating damaged hearts.

With all these possibilities, Blau says researchers should be enthusiastic about both adult and embryonic stem cell work. Even so, she finds herself unhappy that opponents of embryonic stem cell research could misuse her positive findings about adult stem cells to advance their political agenda. She doesn't think adult stem cells can completely replace their embryonic counterparts. "It's important to study all stem cells," she says. "Different diseases may benefit from different cell types."

For his part, Robbins thinks embryonic stem cells have the most potential

for treating damaged heart muscle but still has ongoing projects with

adult stem cells. Repairing the heart muscle after a heart attack is too

urgent to pin his hopes and his patients' hearts on one side of

the debate.

Forget the politics

As long as it can heal, any type of stem cell will do

Projects with adult and embryonic stem cells are showing promise for treating a wide range of diseases.

- Heart attack -- Robert Robbins, MD, associate professor of cardiothoracic surgery, has had promising results from experiments in mice receiving injections of human embryonic stem cells into damaged heart muscle. He and research associate Theo Kofidis, MD, developed a liquid polymer that solidifies when injected and gives the stem cells a structure on which to grow and integrate with the surrounding heart muscle.

- Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases -- Theodore Palmer, PhD, is exploring in rats whether human embryonic stem cells can replace brain tissue damaged by Parkinson's or Alzheimer's.

- Stroke -- Gary Steinberg, MD, has had luck using human fetal brain stem cells to repair stroke-damaged brains in rats.

- Diabetes -- Seung Kim, MD, PhD, has found that human embryonic stem cells can develop into pancreatic islet cells and produce insulin in mice. These could replace islet cells destroyed in people with type-1 diabetes.

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at