|

|

|

|

A quick look at the latest developments from Stanford University Medical Center

![]() Wnts

provide hints for stem cell culture

Wnts

provide hints for stem cell culture

![]() Planning

a new children’s hospital — in San Jose

Planning

a new children’s hospital — in San Jose

![]() Worms

survive space shuttle crash

Worms

survive space shuttle crash

![]() Sleep

legend keeps last class wide awake

Sleep

legend keeps last class wide awake

![]() Bitter

or sweet?

Bitter

or sweet?

![]() Cancer/Stem

Cell Institute update

Cancer/Stem

Cell Institute update

![]() Addicted

to stress

Addicted

to stress

Wnts provide hints for stem cell culture

Scientists have finally laid hands on the first member of a recalcitrant

group of proteins called the Wnts two decades after the proteins’ discovery.

Important regulators of development in multicelled creatures like humans,

these proteins were suspected to have a role in keeping stem cells in

their youthful, undifferentiated state — a suspicion that has proved

correct, according to research carried out in two laboratories at the

medical center.

The ability to isolate Wnt proteins could help re-searchers grow some

types of stem cells for use in bone marrow transplants or other therapies.

What’s more, knowing how stem cells self-renew could lead to ways

of blocking self-renewal

in the cancer stem cells that populate tumors.

Elusive proteins

But Wnt proteins (pronounced “wint”) have proven difficult

to isolate, frustrating those hoping to tap their therapeutic potential.

A protein’s genetic code usually gives researchers clues about how

best to purify it in the lab — but not so for the Wnts. Roeland

Nusse, PhD, professor of developmental biology, figured out why, publishing

his results in the April 27 online edition of Nature. Nusse found that

Wnt’s gene code doesn’t tell the whole story. Although the

code suggests that the protein’s structure should dissolve easily

in water, Karl Willert, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in Nusse’s lab,

found that a fat molecule later attaches to the protein, making Wnt shun

water

and prefer the company of detergents instead.

Finally, pure wnt

With this clue, researchers could finally purify Wnt and confirm previous

hints that the protein helps stem cells maintain their youthful state.

This work, done in collaboration with Irving Weissman, MD, the Karel

and Avice Beekhuis Professor of Cancer Biology, involved cells in the

bone marrow called hematopoietic stem cells that generate all blood cells

throughout a person’s life. Experiments carried out by Tannishtha

Reya, PhD, a former postdoctoral fellow in Weissman’s lab, found

that after a week in an environment containing Wnt, mouse hematopoietic

stem cells were about six times more likely to be dividing than cells

grown in control conditions. What’s more, the majority of cells

in the Wnt-containing environment were still stem cells, whereas their

counterparts had blossomed into a potpourri of other blood cell types.

Additional experiments by Reya showed that other components of the Wnt

pathway also trigger stem cell growth and that the pathway is required

for stem cell maintenance. Reya describes these studies in a second Nature

paper published alongside Nusse’s work. “It’s a big deal

to understand how these hematopoietic stem cells expand their numbers,” Weissman

says. With the ability to grow more stem cells in the lab, researchers

would have a pool of

cells available for research or potential

therapies. — A.A..

| ![]() Back

to Top |

Back

to Top |

Planning a new children’s hospital — in San Jose

Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital and the Silicon Valley Children’s Hospital Foundation have chosen Santa Clara Valley Medical Center as their partner in building a community children’s hospital in San Jose. The first step in the plan, announced in March, is for the three organizations to work with the county of Santa Clara to confirm the financial feasibility of the project and identify the programs and services to be provided at the hospital.

|

|

The vision is to create a children’s hospital that will have between

75 and 100 beds and an adjacent medical office building to house pediatricians

and pediatric specialists. Both would be located on the campus of Santa

Clara Valley Medical Center.

The new facility would be owned and operated by Packard Children’s

Hospital and would likely contract with Valley Medical Center to provide

some support and ancillary services.

“This new children’s hospital will improve access to quality medical care for the children of Santa Clara County,” says Christopher Dawes, chief executive officer of Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital. The main goal of the San Jose children’s hospital initiative is to consolidate what is now a fragmented system of pediatric care in San Jose. The children of Santa Clara County currently are cared for in many different hospitals throughout the region.

If all of the pieces fall into place in terms of planning and feasibility, groundbreaking could occur as early as 2006. Once it is operational, Valley Medical Center’s inpatient pediatric services will be relocated to the new facility. — M.L.

| ![]() Back

to Top |

Back

to Top |

Worms survive space shuttle crash

Nothing was expected to survive the breakup of the space shuttle

Columbia over Texas and Louisiana in February. Imagine NASA’s surprise

when investigators opened five canisters found in the debris field — some

of the 78,000 pieces of wreckage recovered — and found live worms

in each. The small creatures, no larger than the tiniest visible piece

of fuzz on a sweater, were part of a study put together by Stuart Kim,

PhD, associate professor of developmental biology and of genetics, to

see how the worms fared in space.

|

|

The worms, members of the species Caenorhabditis elegans, form one of

the cornerstones of animal model-based biology research (the others being

mice, fruit flies and yeast). Kim has been using C. elegans for years

to ask questions about development and aging. He recently began a collaboration

with NASA scientist Catharine Conley, PhD, to use the worms on the space

shuttle as “canaries in a coal mine,” Kim explains.

“The idea is that we don’t know all the things that are going

on in space. We know that there are cosmic rays and that there are major

changes to the physiology of the astronaut. What’s hard to do is

to make a guess from Earth about all the things that are going wrong

and test them one by one.”

Worms in space

With C. elegans, which has only about 1,000 cells per worm and a genetic

blueprint that has been spelled out in its entirety, figuring out what

is going on is vastly simplified. Kim says the worm’s simplicity

and its similarity to higher organisms makes it ideal for biological

research in space.

The worms’ mission on Columbia was to prove they could grow in space with

virtually no care. If there is anything positive to take from the shuttle disaster,

it is that scientists can be assured they have in C. elegans a proven experimental

workhorse with which to ask questions about how being in space affects life.

Although the future of the space shuttle program remains unclear, Kim says

that through NASA, worms will be making their next space voyage aboard a Russian

rocket. — M.A.B.

| ![]() Back

to Top |

Back

to Top |

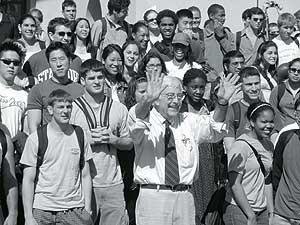

Sleep legend keeps last class wide awake

If you’ve ever met William Dement, MD, PhD, chances are good

that you’ve heard the phrase, “Drowsiness is red alert.” Thousands

of Stanford students and alumni are familiar with Dement’s catchphrase — designed

to remind people of the dangers of sleep deprivation — and a large

group recently belted out those words with Dement one last time.

Sleepy Heads

Dement, the Lowell W. and Josephine Q. Berry Professor of Psychiatry

and Behavioral Sciences, delivered the last lecture of his popular undergraduate

course, “Sleep and Dreams,” March 12. More than 1,000 people,

including many of Dement’s friends and former students, piled into

Memorial Auditorium for the class, which is typically one of the university’s

largest. This quarter, more than 900 undergrads were enrolled; over 15,000

have taken the course since its inception. Dement started teaching the

course 33 years ago, 19 years after working in the lab where rapid eye

movement, or REM, the stage of sleep where dreaming occurs, was first

discovered at the University of Chicago. Dement has spent 50 years studying

and teaching about sleep — earning him the nickname of “Father

of Sleep Medicine.”

|

|

Early in the afternoon class, after announcing that the final exam had

been canceled, Dement led a deafening cheer of his famous catchphrase.

He went on to show videos, including his 1974 appearance on “The

Johnny Carson Show” and another of U.S. Senate Minority Leader Tom

Daschle reciting Dement’s slogan. Pajama-clad members of the Stanford

Band ran on stage and danced with Dement before he said his thank-yous

and good-bye (“Tick-tock, we’ve come to the final moment,” he

sighed).

Dement said there is no single reason for his decision to stop teaching

(“I’ve got to quit some time,” he noted), although the

50th anniversary of the observation of REM “seemed like a good time.”

Despite his retirement from teaching, Dement will continue conducting research and outreach pro-grams and promoting sleep issues in the public policy arena. He said sleep debt contributes to 50,000 deaths a year in the United States and his hope is that people will recognize its dangers and start taking naps when they’re sleepy. — M.L.B.

| ![]() Back

to Top |

Back

to Top |

Bitter or sweet?

Hate broccoli? Now you’ve got a biological excuse. Researchers have discovered a single gene that helps explain why some people love their leafy greens while others simply can’t bear the bitter taste.

|

|

Stanford researchers have helped identify the gene responsible for the

ability to taste phenylthiocarbamide, or PTC. Those who recoil upon tasting

the bitter chemical are called tasters; the rest, nontasters. Tasters

tend to avoid broccoli and grapefruit juice, find spicy food painful

and shun fat.

The research, published in the Feb. 22 issue of Science, also

found variations within the gene that lead some people to be tasters

and others to be nontasters. Stanford’s Neil Risch, PhD, professor

of genetics, statistics, and health research and policy, and graduate

student Eric Jorgenson were among the paper’s authors.

Zeroing in on “ick”

The researchers first narrowed the location of the bitterness-tasting

gene to a region of chromosome 7. Next they sequenced all taste- and

odor-detecting genes in this region. Risch and Jorgenson then analyzed

the data.

When the researchers sequenced the PTC gene in their sample, they found

three genetic changes that related to whether the people were tasters.

Each of these genetic changes caused a molecular switch in the protein

made by the gene. In the most common form of the gene, the protein has

an amino acid designated “A” at the first variable location,

amino acid “V” at the second spot and amino acid “I” at

the third. They called this form of the gene AVI. They also identified

two other forms: PAV and AAV.

People who inherit an AVI version from each parent don’t taste

PTC, while those with a PAV version from each are very sensitive. Those

with one of each can taste PTC, but not as strongly as those with two

PAVs. The AAV version is less clear-cut: Those with an AAV/PAV pair are

tasters, whereas those with an AAV/AVI pair are only somewhat able to

taste PTC.

Still, the PTC gene alone doesn’t account for the full range of how well a person can taste PTC. The range of tasters and nontasters is more like a continuum than a sharp divide: Some tasters seem to taste more than others. What makes up the rest of the story is still unknown, Risch says. — A.A.

| ![]() Back

to Top |

Back

to Top |

Cancer/Stem Cell Institute update

|

|

The School of Medicine’s plan to establish a new Institute

for Cancer/Stem Cell Biology and Medicine, announced in December, fueled

the ongoing national debate regarding stem cell research. In recent months,

Dean Philip Pizzo, MD, and the institute’s director Irving Weissman,

MD, have worked with the Communication & Public Affairs staff to

explain Stanford’s involvement and perspectives on the issue. By

speaking with reporters and policy-makers, organizing symposia for researchers

and the general public, and publishing articles — including an op-ed

in the San Jose Mercury News — the School of Medicine is getting

out the word.

One key outreach effort was the annual Beckman Symposium. This year’s topic “Stem Cells, Regenerative Medicine, and Cancer” brought together many of the word’s leading scientists, including former NIH director Harold Varmus, MD, to discuss the latest in stem cell treatment, tissue replacement and regenerative medicine. The two-day symposium on April 14-15 drew members of the general public and hundreds of scientists. The Communication & Public Affairs office has gathered online resources offering Stanford’s view on the issues and links to sites with information about the science and politics of stem cells. On the Web see mednews.stanford.edu/stemcell-index.html. — R.S.

| ![]() Back

to Top |

Back

to Top |

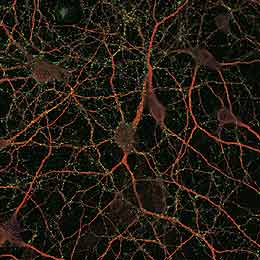

Addicted to stress

|

|

| A tangle of neurons with synapses stained green | |

Drug addicts vary in their drug preferences, but their brains have

something in common. All addictive drugs tweak the same addiction-related

neurons, causing them to become more sensitive. Furthermore, stress leads

to the same changes in these neurons.

Robert Malenka, MD, PhD, the Nancy Friend Pritzker Professor of Psychiatry

and Behavioral Sciences, is the senior author of a paper in the Feb.

20 Neuron, which describes the molecular changes that occur as a result

of taking addictive drugs and experiencing stress.

When people take addictive drugs, neurons in the ventral tegmental area,

a region that perches atop the brain stem, ramp up production of the

neurotransmitter dopamine. The new research shows that the drugs also

increase the sensitivity of these neurons to the chemical glutamate,

which triggers dopamine production. Researchers suspect it’s the

release of dopamine in addition to this enhanced sensitivity that leads

to addiction.

The researchers also found that stress triggered an identical set of changes

in the brain.

Malenka pointed out that while stress itself might not be addictive, it can trigger a reformed addict to slip. “When drug addicts who are in remission and are doing fine are subject to stress, they very often relapse,” he says. The current work could help researchers understand the link between stress and addiction.

In the long term, this work might lead to drugs that block the addictive response, he says. — A.A.

| ![]() Back

to Top |

Back

to Top |

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at