|

|

A Stanford surgeon advocates a strategy for early detection of anal cancer

By Amy Adams

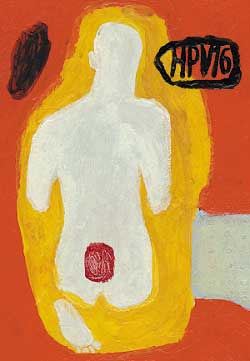

Illustration by Brian Cairns

Photograph: Trujillo/Paumier

Yearly trips to the doctor's office are riddled with screenings – most of them unpleasant. First there's an annual exam for skin cancer, then there are colonoscopies, pap smears, mammograms and prostate tests, depending on a person's age and gender. So when Mark Welton, MD, decided to add anal cancer screening to his patient checklist, he thought he was building on accepted practice – that of detecting and treating adolescent cancers before they progress to full-fledged disease.

"The other option is to not treat the patients and let them get cancer," says Welton, an associate professor of surgery. Of these two choices, Welton sees early detection as the clear winner.

The trouble is that the same doctors who advocate regular screening for breast, colon, cervical and skin cancers haven't welcomed Welton's technique for anal cancer screening. They don't follow the reasoning he uses to explain why his technique works and many feel that because the cancer affects a small group of people – primarily men who have had sex with men – the widespread use of his technique is unnecessary.

Despite this resistance, Welton has been screening high-risk patients and treating early disease, quietly ignoring his detractors and arguing his case at medical meetings when the opportunity arises. Although change comes slowly, he has noticed an increase in doctors contacting him for more information, and has had doctors visit from as far away as Australia to learn his technique. Some who have heard him speak are responding by referring high-risk patients to Welton for screening – with patients coming from Los Angeles, Eureka and outside California.

Welton's reasoning for anal cancer screening hinges on two observations – that anal and cervical cancers are caused by the same virus and that the two tissues undergo similar changes on their path from early abnormalities to cancer. He figures that if anal and cervical cancers have such similar origins and appearances, the same techniques could be used to detect and eradicate early signs of disease. These techniques include a regular Pap smear and then removing any suspect tissue.

"I've spent my career arguing that cervical and anal cancer are similar," Welton says. If he's right, Welton may see the same reduction in anal cancer as doctors in the 1940s saw in cervical cancer after Pap smears hit doctors' offices. Cervical cancer plummeted from 350 cases per million women – roughly the same as the rate for anal cancer in men who have had sex with men – to only 70 cases per million women today.

The bottom line: Who's at risk?

The virus that lies at the heart of both cervical and anal cancer is the human papilloma virus, or HPV – the same virus that causes genital warts. Welton says that almost all people are infected by the virus through sexual contact, but that most people's immune systems eradicate the virus before it does any damage. Of those who don't fend it off, some go on to develop genital warts, but others never show obvious signs of their infection. Instead, the virus lurks unnoticed in the cervix, anus or at the base of the penis or scrotum where it can easily spread to new sexual partners.

Currently, only nine women and seven men per 1 million get anal cancer. But among men who have had sex with men, the rate is 350 cases per million people, and that goes up to 700 per million in HIV-positive men who have had sex with men. Welton expects that number to increase as HIV-infected individuals live longer with compromised immune systems.

Women who have had cervical cancer – and are therefore likely to be infected with a virulent strain of HPV – and their partners who have been exposed to that virus are also at increased risk of anal cancer, as are people who have had transplants and are on immune-suppressing drugs that could allow the virus to resurge.

Making an argument for screening and treating

When the human papilloma virus infects cells, it produces several proteins that help the virus divide and infect the cell. Two of these proteins can also interfere with the cell's normal controls on cell division. Although there are hundreds of different types of HPV, one particularly nefarious subgroup – HPV 16 – wreaks the most havoc with cell division and is the most commonly found HPV strain in tumors. What's more, HPV 16 and other virulent groups generally do not form warts so people are not alerted to their infection.

Over time, the genetic changes caused by uncontrolled division can lead to a precancerous condition called dysplasia, which is the condition that a Pap smear detects. In a Pap test, the doctor wipes a swab over the cervix to pick up loose cells, smears that sample on a glass slide and then studies it under a microscope. Normal cells form a tidy pattern of organized tissue. In dysplasia, cells with an unusual shape disrupt this regular pattern – the more disruption the more severe the dysplasia.

One argument Welton makes for why anal and cervical dysplasia are similar – aside from their appearances under a microscope – is that both types of dysplasia tend to occur in similar regions of their respective tissues, a region known as the transition zone. This transition occurs between the tall, narrow columnar cells that line the uterus or upper portion of the anal canal and the flat sheet of squamous cells covering the outside of the cervix or the lower portion of the anal canal. This zone, where columnar cells are constantly being formed into squamous cells, is where doctors traditionally take the Pap smear.

In addition to having a dysplasia-prone transition zone, both tissues undergo similar changes as the dysplasia turns into cancer. In March 2000 Welton published a study in Diseases of the Colon and Rectum showing that both tissues experience an explosion in cell numbers during the precancerous phase, and both tissues have new blood vessels threading throughout to support these new cells. To add to the population explosion, fewer cells die in precancerous tissue than in normal tissue.

To Welton, the similarities between precancerous changes in the tissues add up to one thing: a protocol that detects and blocks those changes in one tissue is bound to work in the other. Following that logic, Welton and his colleagues thought that an anal Pap smear would be just the thing for detecting early anal cancers. Sure enough, when they sampled cells within the anal transition zone of high-risk patients, they discovered many cases of dysplasia. When Welton tested those abnormal cells, almost all of them were infected with HPV. To Welton and his colleagues, the obvious next step was to remove the cells before they become cancerous, using as his model the technique surgeons use to remove cervical dysplasia.

Welton first stains the anal tissue with a combination of dyes that turns normal cells a dark brown and leaves HPV-infected cells a lighter color. He calls this phase anal cartography because it maps the location of abnormal cells. Welton then removes a small sample of the light-colored tissue for a biopsy and burns the remainder with a scorching hot needle. In a paper Welton published in April 2002 in Diseases of the Colon and Rectum he followed 37 patients after their abnormal cells were removed to discover whether the surgery had negative side effects. He found no anal incontinence, no infection, no significant bleeding and no decrease in sexual enjoyment in his patients.

Welton admits that anal cartography and surgery are far from his patients' favorite procedures. Some have said that on a scale of one to 10 – with one being blissful comfort – their pain from the surgery pegs out at 20. New drugs on the market help reduce the misery, but it's still a difficult recovery.

"I tell my patients, 'Imagine putting your hand on a stove – it's going to hurt.' That's what we're doing to your butt," Welton says.

Welton's detractors argue that nobody has proved the value of removing these abnormal cells – he hasn't, for example, labeled a cell that he'd normally remove and instead left it alone and watched it become cancer. Because of this, some doctors argue against the merits of dealing with newly discovered dysplasia, especially because the removal process is so painful.

Welton points out that nobody has watched cervical dysplasia become cancer, nor has any study monitored colon polyps to verify that they become cancerous or monitored abnormalities on a mammogram until cancer evolves. Instead, doctors remove the suspect tissue and have seen cancer rates decline.

"In every other organ system we treat precancerous conditions. Why not treat this?" Welton asks. As for the surgery being painful, Welton says, "There's a bazillion things we do that hurt, so that's not a good argument. We're preventing cancer rather than just watching it."

Welton doesn't have the one piece of data that would settle his detractors' minds once and for all – clinical trial data comparing anal cartography to no treatment. But he does have some anecdotal evidence: Over the past several years of doing anal cartography he's had no patients develop anal cancer. "No colorectal surgeons who believe in observation rather than anal cartography can say that," Welton says.

|

|

"In every other organ system we treat precancerous conditions. Why not treat this?" |

|

Revolutionary, yes. But is it good medicine?

A bona fide medical advance isn't always easy to spot

When you take your ache or pain to a doctor, the advice you get is based on solid facts, some good studies, and it bears the stamp of approval from that doctor's medical organization. Right?

Not necessarily. "Medicine is not cold and analytical," says colorectal surgeon Mark Welton, MD, an associate professor of surgery. "It is very emotional." Welton says that what drives doctors to try new procedures is a matter of what they hear at meetings, what they read in journals, and what resonates with their own internal "medic-o-meter."

"It's also driven by what patients want done," Welton says. "If enough patients come in wanting a procedure and you say no, then you lose patients. It's all very patchwork."

Doctors like Welton who advocate a new approach to patient care spread the word by publishing studies, talking at meetings and waylaying colleagues in the hallway to discuss the technique. This is the networking approach to patient care. Doctors who opt out of attending a medical meeting or go to a different session might miss out on learning about a useful treatment.

Welton says that distinguishing the truly revolutionary techniques from the less scientifically sound alternatives is difficult, even for experienced physicians. "It's hard to tell what's truth," he says. When Welton talks at meetings he relies on his published studies to set anal cartography squarely on the side of the believable rather than the "fly-by-night" techniques.

Over time, if a technique works well enough, patients will come to expect it as part of normal care and most doctors will accept that new approach. Even so, doctors need to be able to choose the best approach for treating each patient. "Medicine isn't a textbook that you open up," Welton says. "Often there's more than one right answer."

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at